Brooklyn Democratic Party leaders voted to hold fewer meetings and restrict member-driven resolutions on Jan. 20 — two changes that reformers claim will reduce the body’s transparency.

“They’re just obvious tools to disengage people,” said Jessica Thurston, the Vice President of Political Affairs at the reform-minded New Kings Democrats. “It consolidates power and reduces accountability.”

At a closed-door meeting, the Executive Committee of the Kings County Democratic Party — which is made up of 46 district leaders, one male and one female from each of the borough’s assembly districts — voted to enact the two rule changes, causing an uproar among their fellow Democrats, according to one district leader who spoke on the condition of anonymity.

“It really sparked a very fierce, contentious conversation,” the person said.

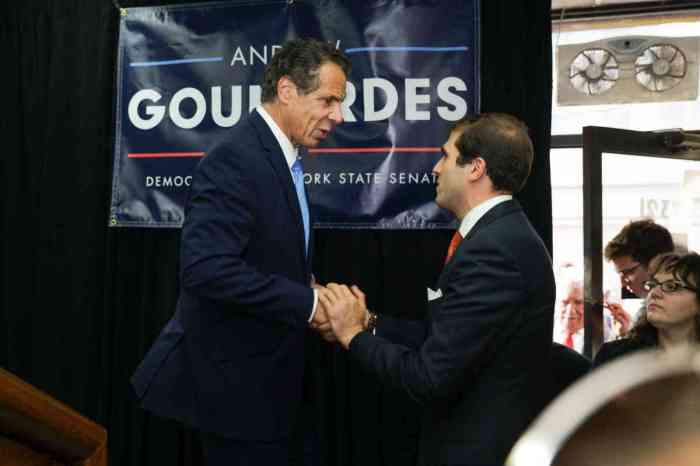

The amendments come amid a change of guard atop the organization’s leadership, as outgoing party boss Frank Seddio announced that he would be stepping down earlier this month, and backed Assemblywoman Rodneyse Bichotte (D-Flatbush) as his successor.

Just before her fellow district leaders officially made her the new chairwoman of the party, however, they passed the two controversial amendments.

The first resolution reduced the number of times that the county committee convenes, from twice yearly to just once.

The second change limits the scope of member-introduced resolutions — proposals introduced by average Brooklyn Democrats to make changes within the party establishment — so that they can’t address “any aspect of the internal governance” within the party.

Both reforms negatively affect citizen participation in party governance by curtailing the ways in which average citizens can make their voices heard, according to one district leader, who expressed optimism that the changes could be undone.

“Folks like myself, and other reform coalitions, fought really hard to create additional avenues and additional meetings for the conduct of party business,” said Doug Schneider, whose district includes Park Slope and Windsor Terrace. “It remains my hope that this is not a permanent change.”

Party leaders told attendees that reducing meetings was a necessary step for the cash-strapped party, which had just $40,327 in its account as of Jan. 15, and is $226,000 in debt, filings show. Executives claimed the party couldn’t even spare the money for postage to announce the meetings by mail — let alone front the cost of the events’ venue.

Seddio, who declined to comment for this story, has claimed in the past that the low finances were a result of the party declining donations from the real estate industry.

Some critics argue that paying for the meetings — such as the last one in September 2019 at the Coney Island Amphitheater — is a drop in the bucket compared to other party expenses.

But even if cost restraints limited the number of meetings, other critics argue that a lack of funds doesn’t explain the committee’s vote to restrict the power of resolutions — a change that limits members’ ability to implement changes to the party, Thurston claimed.

“It’s the primary tool that allowed members to participate and be engaged,” said Thurston.

Resolutions have always been non-binding “statements of aspiration,” Schneider explained, but many held power.

One member-driven resolution that passed at the September meeting called for the creation of a finance committee to audit the party’s spending and low funds, which was set to present their findings at the following meeting scheduled for February — but that gathering is now canceled, and there’s no evidence that such a committee was even created, the reformers claim.

Convenient that the meeting where the party was bound to disclose their audit to the members is now cancelled.

— Brandon West (@brandonwestnyc) January 24, 2020

Schneider — who clarified that he thinks “the new chairperson is amazing” — said that grassroots organizers now must pressure their district leaders to seek change on their behalf, and worried that the two amendments marked an unfortunately undemocratic start to Bichotte’s tenure atop the Democratic party.

“The biggest thing for me is that these amendments were passed in the minutes before we elected a new chairperson,” he said.

Others bemoaned the general lack of transparency of the entire process, which occurred at the seminal Jan. 20 meeting with only five days’ notice and on Martin Luther King Day.

“The process by which [Bichotte] was chosen was very hasty and not transparent,” said Josh Skaller, a Brooklyn Heights district leader who couldn’t make the meeting. “I was already out of town on business.”

Bichotte did not return several requests for comment.