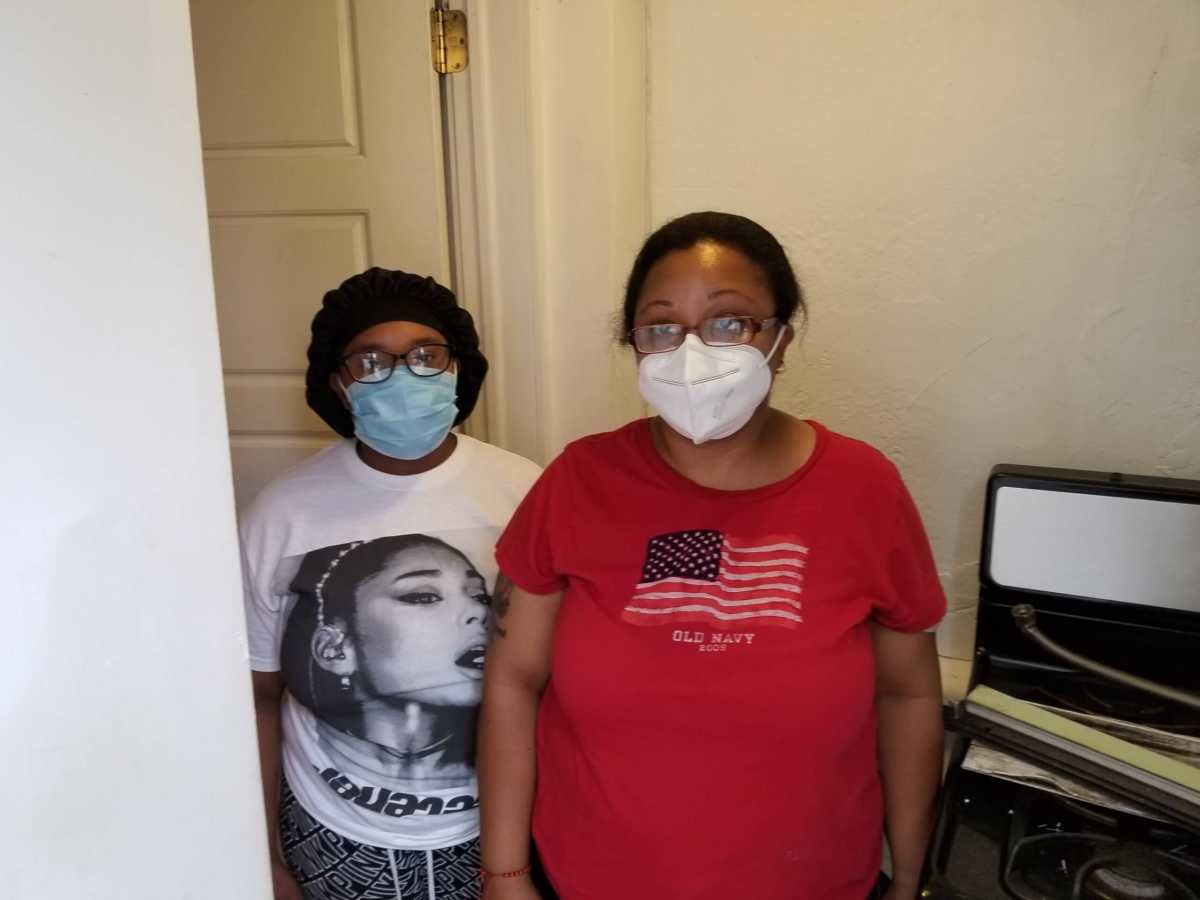

For several years, Erica Samuels has shared her Brownsville basement apartment with her college-age daughter Janeé, her 11-year-old pit bull Dominic, and a guinea pig named Angelica. But recently, the roach and rodent problem has become so perverse that she has taken in a cat off the street, whom she has nicknamed Lucky.

Samuels, a 43-year-old health care worker and Marine Corps vet, has lived at 15 Monaco Place (between Atlantic Avenue and Herkimer Street) since 2020. But unlike the eponymous European microstate, whose tourism slogan is “For You,” her tenancy has been anything but to her liking, and now to cap it all off, she is facing eviction and homelessness if she loses her case in Housing Court this week.

Samuels moved in while she was unemployed and amidst the state’s moratorium on evictions. Almost immediately, things started to go wrong. A couple weeks after moving in, her stove repeatedly leaked gas into the cavernous abode with few windows. Diagnosed with a defective knob, the appliance was removed and placed in her doorway, but she says the landlord refused to replace it, leading Samuels to eventually purchase one of her own for $1,300.

Unfortunately, some other residents have also made home behind the stove: mice, who enter through a moldy hole in the wall and whose midnight snack runs have forced Samuels to cease leaving food on her counter for any length of time. Elsewhere, roaches have burrowed into the nook housing the gas meter, while mold has coalesced on surfaces all over the home.

“I’m allergic to the mold,” Samuels told Brooklyn Paper. “So I have to take pills to breathe.”

The poorly-ventilated apartment is scorching during the summer and freezing during the winter. Like many other basement apartment dwellers, her home suffered significant flood damage during Hurricane Ida but she claims that the landlord “didn’t even check up” on her.

Inspectors from the city’s Department of Housing Preservation and Development corroborated Samuels’ claims last summer. When Brooklyn Paper visited the home this week, the problems persisted.

The landlord, Ariel Rubio, has refused to fix any of it, Samuels says, though he lives right upstairs.

Despite the decrepit state of the apartment and the ongoing pandemic, Rubio told Samuels that her lease would not be renewed for another year after its expiration in September 2021. When she refused to leave, Rubio charged her double her previous rent, jumping from $2,100 to $4,200. Samuels refused to pay the new rent, believing it to be illegal, and continued to pay her old rent using state funds via the Emergency Rental Assistance Program (ERAP), which were approved despite the doubled rent.

But with the eviction moratorium over since January of this year, a judge in April authorized Rubio to evict Samuels by June 22, arguing she owes over $35,000 in rent arrears since she has only paid half the rent since September; that order was later stayed pending another court hearing this Thursday, July 7.

She was already planning on moving out, anyway: she has a lease contract for a new place but cannot move in until the end of this month, when the previous tenant leaves. But if she loses in court on Thursday, she says she’ll be homeless for the next few weeks.

“They’re making it seem like I’m trying to stay here,” Samuels said. “I’m not trying to stay here, there’s too many issues. But I don’t want to be homeless. Just give me a few weeks!”

“I’m in the process of getting this new house,” she continued. “But there’s things that need to be taken care of before my family moves.”

Samuels is in a similar boat to tens of thousands of New Yorkers who, since January, have once again faced eviction from their apartments. As of July 1, New York City landlords have filed nearly 47,000 evictions against their tenants in Housing Court in 2022, according to state court system records. That includes 12,772 in Brooklyn.

But because evictions could not be authorized under the moratorium, cases filed in 2020 and 2021 are only now making their way through Housing Court. More than 123,000 evictions were filed in 2020 and 2021 in the Big Apple.

Evictions usually take a long time in New York, longer than most places in America, and can only be executed with authorization by a judge; strict regulations are supposed to protect tenants in arrears from retaliation or from being forced out extra-legally. But the sheer breadth of evictions going through the machine has overwhelmed the system such that many tenants are being forced to go in front of a judge without a lawyer, in violation of the city’s right-to-counsel law.

In spite of that, Housing Court operations have soldiered on; a spokesperson could not provide a hard number on tenants who have gone to court without a lawyer this year, but estimated it in the hundreds.

Esteban Girón, an organizer with the Crown Heights Tenant Union and Brooklyn Eviction Defense, said that the two-year eviction moratorium had shown that another world was possible, one without the trauma and brutality that come with evicting people.

“We’ve been told for our entire lives, if rent and evictions were abolished, the entire system would completely collapse,” said Girón. “But we just got out of two years of a moratorium and the system didn’t completely collapse.”

The moratorium certainly impacted what tenants and the tenant rights movement thought was possible, Girón says. But his group is now right back to organizing direct actions against landlords illegally locking out tenants or going to court to support people as they go before judges, a disappointing turn after seeing what was possible, and he fears that the eviction crisis is only going to get worse.

“We’re moving in a good direction,” Girón said. “But I think people are underestimating how big the crisis would’ve been [without the moratorium], and how big it’s still gonna be.”

The return of wide-scale evictions has coincided with Brooklyn and citywide rents climbing to record highs after a brief pandemic-era dip. Median rent in Brooklyn hit at an all-time high of $3,250 in May, according to real estate firm Douglas Elliman; the sky-high value of leases has forced many market-rate tenants out of their apartments, especially those who moved in during the pandemic paying a discounted rate.

Meanwhile, the Rent Guidelines Board last month approved lease hikes for the city’s 2.4 million rent-stabilized tenants of up to 5%, the largest hikes since the Bloomberg era and against fierce opposition from tenants, advocates, and elected officials.

Rubio’s lawyer, Marc Hyman, dismissed Samuels’ contentions, arguing that she was being evicted for overstaying her expired lease. He said that Samuels’ eviction was “not newsworthy” because “people get evicted every day,” but that Samuels’ refusal to leave had had a tremendous impact on his client, Rubio, a small landlord.

“She should have been out last September,” Hyman said in an email. “What about my client’s rights? What about a tenant having to abide by their contractual responsibilities and obligations?”

Hyman says that “no one forced [Samuels] to stay” in the apartment after the lease expired, and claims that she only started filing lawsuits for repairs after she was told to leave (Samuels first filed a lawsuit urging repair in June 2021, and says she was told of the non-renewal following a court date).

Samuels, who claims she’s been dealing with a derelict landlord since the beginning, says that she wasn’t given the opportunity to try to find housing before Rubio started trying to evict her, finally finding a new place just days before her scheduled eviction.

“I’m gonna be homeless,” Samuels said. “That’s why I need an extension to the end of this month. We do have a place, but the place is not ready.”

A rep for HPD did not respond to a request for comment.