What do Sunset Park, Staten Island, Lower Manhattan and Coney Island have in common? The Towers of Bay Ridge!

The twin cooperative high-rises at 65th Street and Fourth Avenue may be neighborhood icons — but they are political pariahs, plucked from Bay Ridge by Albany power brokers and thrust in far-flung districts to be represented by a disparate array of lawmakers.

And that’s a problem for those who claim that a Ridge-based pol would better meet the needs of the over 2,000 residents who live in the hulking 30-story buildings.

“We don’t have any interaction anymore with our elected officials,” groused Linda Orlando, a resident of the complex since 1974.

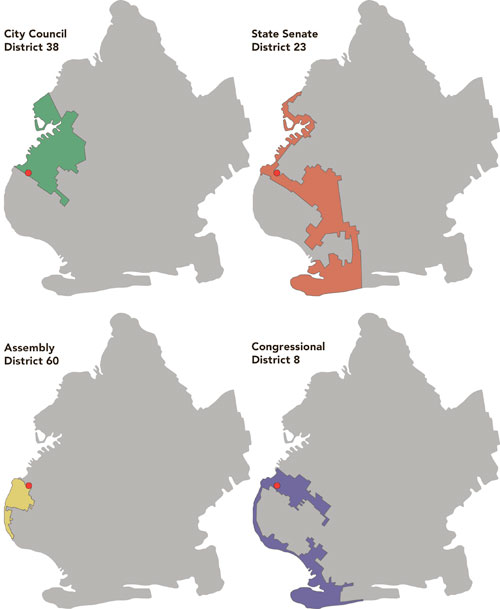

That could be because the lawmakers have a lot of travelling to do throughout their sprawling and oddly configured districts — which just so happen to include the towers. State Sen. Diane Savino’s mostly Staten Island district includes a tiny portion of southern Brooklyn. It’s the same for Assemblywoman Nicole Malliotakis’s mostly Staten Island district, which touches a bit of Bay Ridge.

Rep. Jerry Nadler’s district is often called “the Nathan’s to Zabar’s district” because it snakes from Coney Island to the Upper West Side, slicing through a tiny portion of Bay Ridge.

And Councilwoman Sara González’s district is almost entirely Sunset Park and Red Hook — plus the Towers.

And some residents believe that they have extra difficulties when they need the city to install a traffic signal, getting a pothole fixed or having any number of other “local” issues addressed.

Every 10 years, a state commission redraws district lines based on new Census data, adding or subtracting seats based on population shifts so that each district in the state or city contains a set number of constituents.

In East New York, for example, population declines recorded in 2000 forced mapmakers to tack on the northern half of Canarsie to the Assembly district to meet their mandate. And Staten Island, for example, shares its congressman with Bay Ridge because its population is too small to support its own federal lawmaker.

And there’s plenty of wiggle room to create districts that protect incumbent and party interests.

In 1980, for example, a Democrat-controlled Assembly eliminated Bay Ridge’s single Assembly seat, held at the time by Republican Florence Sullivan. The neighborhood was then carved into five majority-Democrat districts.

“The Democrats in the Assembly eliminated any hopes of the Republicans having a seat in Bay Ridge,” said former state Sen. Marty Connor, who represented Brooklyn Heights for 30 years.

Towers Ping-Pong was played in the 1990s when the buildings were “accidentally” placed in Connor’s district. “It took four years for anyone to figure that out,” he recalled.

Connor was one of the people in the room when district lines were carved out.

“The Towers were voting Democratic so there was a desire [by the Republican-controlled Senate] to get them out of the Bay Ridge senate district which had been Republican. It’s all politics,” he said.

Board of Election data confirms the trend: in both the last presidential and gubernatorial races, the Towers voted decidedly Democratic.

Redistricting brought change to the sprawling complex — at least in spirit.

“They lost their identity,” said Jane Kelly, member of the board of directors for the Bay Ridge Community Council, a civic group calling for a non-partisan redrawing of district lines.

Activists said the fight is now on to re-enfranchise the Towers.

“Political representation is not as adequate paired with other neighborhoods and other boroughs,” declared Kevin Peter Carroll, a district leader for the 60th Assembly District, who supports a single Assemblymember for Bay Ridge and intends to make the Towers a key staging area for a neighborhood-wide initiative on the matter.

“People in the Towers consider themselves from Bay Ridge — not other areas,” he said.

Carroll might be buffered by former state Sen. Seymour Lachman (D–Bensonhurst), who is also calling for redistricting reform.

“The neighborhood and the Towers are better served if they are together than taken out of the district for a few votes,” said Lachman, who is now director of a government reform center at Wagner College. “In general, I don’t believe in breaking up a neighborhood and dividing them. I believe in contiguous districts and not gerrymandering.”

But not everyone was convinced. A random sampling of residents coming to and from the buildings last Friday revealed that most residents could care less who represents them.

“It’s not an issue for me,” said Margaret McQuade, joining a chorus of towers residents.

Political veterans weren’t surprised.

“It’s not about having someone in your neighborhood, it is about having people in the neighborhood pester whoever it is to do the work,” said longtime political consultant Hank Sheinkopf. “The way you get government to respond is to force them to respond.”

But incumbent pols didn’t reject the notion that a cohesive district would mean better government.

“Anyone who needs assistance get it, but it would be easier for them if they could have a representative they can access in person quicker,” said Savino, whose district office in Brooklyn is in Coney Island.

Towers residents conceded that their pols aren’t necessarily doing a bad job — that is, if they could correctly identify them.

When asked who her congressman is, Ann Smyth seemed quite confident with her answer: “Vincent Gentile — he comes to my kids school,” she said, referring to a Bay Ridge councilman.

And he’s not even hers!