A bill seeking to curb New York’s use of high-polluting concrete was signed into law by Gov. Kathy Hochul last week, a move activists hope will create a domino effect on other states seeking to make their infrastructure more green.

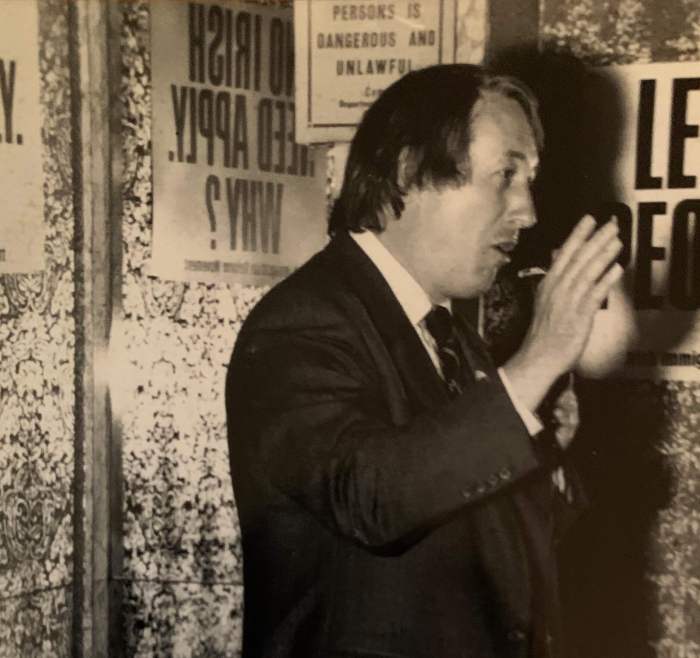

“Seven percent of global CO2 emissions comes from the production of concrete,” said Brooklyn Assemblymember Robert Carroll, the bill’s sponsor. “New York cannot meet its goal of reducing carbon emission by 85 percent by 2050, if it does not create a standard to decarbonize concrete.”

Concrete is one of the most-used materials in the world, second only to water, and the production of cement, concrete’s primary binding agent, is a major source of greenhouse gas emissions in the US. At least 67 million tons of carbon dioxide equivalents were produced by cement plants, like the Lefarge Ravena plant near Albany, in 2019, according to the federal Environmental Protection Agency, 10 percent of total emissions reported by the country’s industrial sector.

“It’s a very major source that receives much less attention than it deserves,” Michael Gerrard, founder of the Sabin Center for Climate Change Law at Columbia University, told Brooklyn Paper. “And I think that there’s intense interest in coming up with standards that can be adopted and applied.”

It is possible, if not popular, to use alternative concrete-production methods with lower emissions, and concrete with lower carbon footprint than “traditional” concrete is considered “low embodied carbon” concrete.

Carroll’s Low Embodied Carbon Concrete Leadership Act orders the state’s Office of General Services to create an advisory group of government officials and industry and environmental leaders, who will develop and issue a standard for what can be considered low embodied carbon concrete. Those standards will be used in publicly-funded construction, hopefully reducing the impact of new state infrastructure and making lower-carbon options more popular.

Gerrard was concerned about the makeup of the advisory group, which will have only one representative from the state Department of Environmental Conservation, among a host of engineers, architects, and representatives from the construction and concrete testing industries. The bill does not seem to plan a public comment period for the standards once they are developed and published, he said.

“The committee is dominated by the construction industry,” he said. “[Public comment] would allow experts from outside that industry to have input and put forth technical and environmental issues that the members of the committee might underplay. This bill is a positive but imperfect step in the right direction, and the devil is in the details, and there are many details ahead of us.”

An earlier version of the bill included a tax credit for contractors who used low embodied carbon concrete, but that credit was removed before the final version passed through the state legislature.

“With the enactment of this bill, New York creates a framework to reduce the carbon footprint of concrete and positions the state to be a world leader in environmentally friendly concrete production,” Carroll said. “By requiring state projects to meet certain low-embodied carbon concrete standards, New York’s roads and buildings will be greener and influence how other states and private industry build.”

Portland, Oregon, is in the midst of developing low-carbon concrete standards after a 2019 analysis revealed the high emissions output of the city’s construction business. Starting in 2022, city-funded construction projects will be expected to abide by those standards.

“[This] law puts concrete on New York State’s larger climate policy radar, and none too soon,” said Chris Neidl, co-founder of the Open Air Collective and a former director at Brooklyn SolarWorks, in a release.

The use of concrete in New York and nationwide is likely to increase in coming years, Gerrard said, in part because oncrete is often used for building defenses against sea level rise and for constructing buildings that are resistant to wildfires. While he wants government and industries to search for more-sustainable alternatives to concrete, it’s hard to find another material with the same useful properties. The recently-signed $1 trillion federal infrastructure will boost new construction, most of which will be carried out by state governments and which will contain, of course, concrete.

New York’s Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act aims to cut the state’s greenhouse gas emissions by 85 percent in 2050, and Hochul and state agencies have been taking that goal seriously, rejecting permits for natural gas power plants that wouldn’t adhere to emissions goals and announcing plans to expand access to renewable energy downstate.

Earlier this month, Eastern Generation, one of the city’s most relied-upon power companies decided to pull their application for new fossil fuel infrastructure in Sunset Park, telling Brooklyn Paper that the process to get the project approved had already been “extremely difficult.” The company will begin turning toward renewable energy ahead of schedule instead.

The decision came just after the City Council approved a law banning natural gas hookups in new construction. Last month, two other local legislators, Assemblymember Emily Gallagher and state Sen. Brian Kavanagh, introduced a bill that would ban gas hookups in new buildings statewide.

“It has to be addressed if we are going to succeed in our broader emissions goals. But today’s win is only a start,” Neidl said. “The stage is set and we need to work diligently to ensure that the assembled advisory group recommends a program based on best practices, and is designed for impact and innovation, not half measures and the status quo.”

Outside of the potential to influence other states and private industry, Gerrard said the government should be turning their regulatory gaze to other commonly-used, high polluting materials.

“Public procurement presents tremendous opportunity to help us achieve our climate goals,” he said. “This sort of standard, I think, is very important. I’d like to see it also applied to steel, aluminum, paper, and other emissions-intensive products that the government acquires in large quantities.”