Hundreds of New Yorkers descended upon City Hall on Wednesday in to voice their opinions on Brooklyn Council Member Chi Ossé’s bill to shift the onus of costly broker fees off of tenants and on to landlords.

Intro. 360, also known as FARE Act —Fairness in Apartment Rental Expenses — would require whoever hires the broker to pay the fees. More often than not, it’s the landlord who has hired the broker, but the renter who must absorb the sometimes-exorbitant fees.

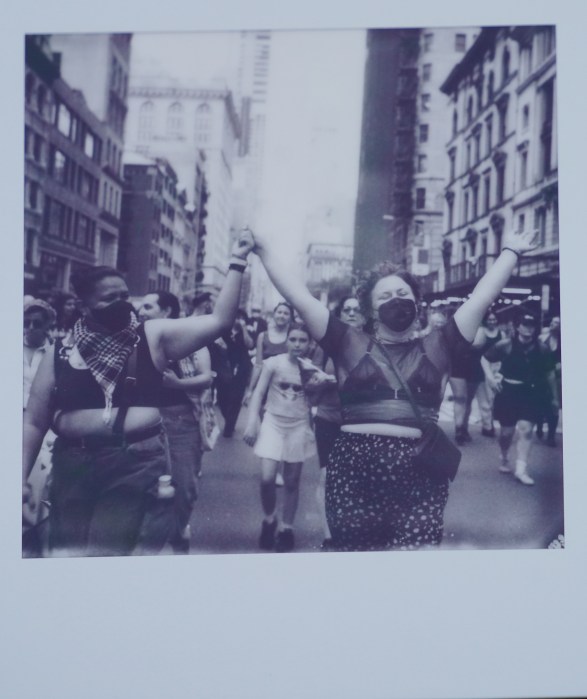

On June 12, hundreds of New Yorkers testified at an hours-long City Council hearing on the bill. Supporters said high broker fees burden New Yorkers looking for new apartments, sometimes to the point that they opt not to move at all. Detractors, though, said the bill would put brokers out of a job and raise rents across the city.

The cost of broker fees

Two-thirds of New York City’s residents are renters, most of whom have had firsthand experiences with stressful and frustrating apartment-hunting processes. In many instances, that process includes paying a broker fee to a licensed real estate agent hired by the apartment owner to arrange showings of the homes.

Broker fees range from one months’ rent to 15% of the annual rent or more. When looking for a place to live, many tenants’ experiences are limited to finding an available apartment online, arranging one visit, and putting together an application, all on their own. They sometimes never meet a broker but pay the fees the landlord agrees to.

“People can’t afford their rent and people certainly can’t afford an additional $2,000, $3,000 to a broker they never hired,” said Ossé, who represents parts of Bed-Stuy and Crown Heights, at a rally ahead of the hearing.

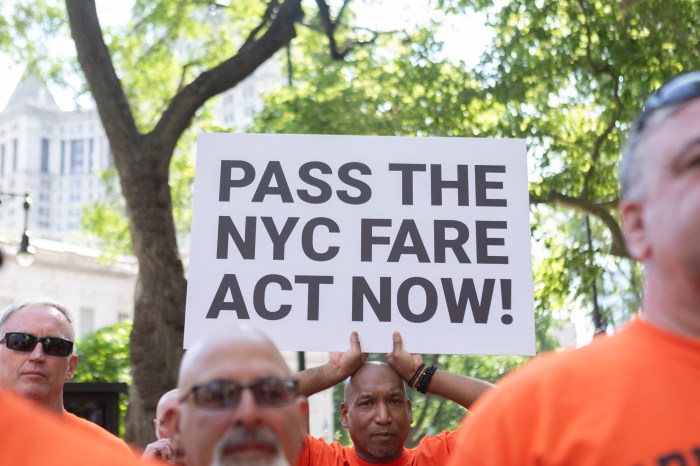

The line to get into the meeting wrapped around the block — full of bill supporters holding signs that read “End Forced Broker’s Fees” and “Pass the Fare Act Now” as well as opponents, including many members of the Real Estate Board of New York, who held signs that said “Agents Are Tenants Too,” and “Don’t Raise the Rent.”

Detractors of the bill say that if landlords are forced to pay the broker fee, they will simply pass on the expense to the tenant in the form of higher monthly rent.

In his opening statement, the Ossé tried to appease renters worried about costly rents.

“Rent is determined by market forces, not landlords,” he said “If a landlord could magically raise your rent by several thousands of dollars tomorrow, he would have done so yesterday.”

At the hearing, which was hosted by the council’s Committee on Consumer and Worker Protection, there were no officials from the city’s Department of Consumer and Worker Protection or any representative from the city’s administration who could provide data to support or oppose the bill.

The Adams administration instead sent a representative of the city’s Department of Housing Preservation and Development — drawing criticism from lawmakers.

“This is a literal waste of time,” said Brooklyn Borough President Antonio Reynoso, who called the FARE Act a “common sense bill.”

“We are going to be relegated to having a conversation that we already had in the public,” he said. “We are wasting time. (…) I don’t even know if anyone from the administration has stayed to listen to the testimony of all these people who deeply care about this issue.”

New York City’s housing crisis

Reynoso rebuffed claims that the bill would increase rent or worsen the city’s housing crisis.

“No one here, not even the landlords, needs to tell me that we are experiencing a housing crisis, but because we are not building enough,” he said.

According to the most recent city data, New York City’s vacancy rate is at a historic low of 1.4%, the lowest it has been since 1968.

In a statement released in February, when the data was presented, HPD called for “urgent action and new affordable housing.” It added that “without significant public investments in new construction and housing preservation, the city’s wealth gap and racial disparities will grow while middle—and low-income New Yorkers will increasingly struggle financially.”

Reyoso shared his experience of having to put down a security deposit and a broker’s fee in one payment of $7,500 to get his apartment in 2009 without ever meeting the broker.

“It was very difficult for me who is well off, middle class,” he said. “When I was a council member, it was very difficult. Those challenges are real for people who experience it. Paying $1,000 instead of $5,000 would have made a big difference for me and my family.”

Some brokers stand against the FARE Act

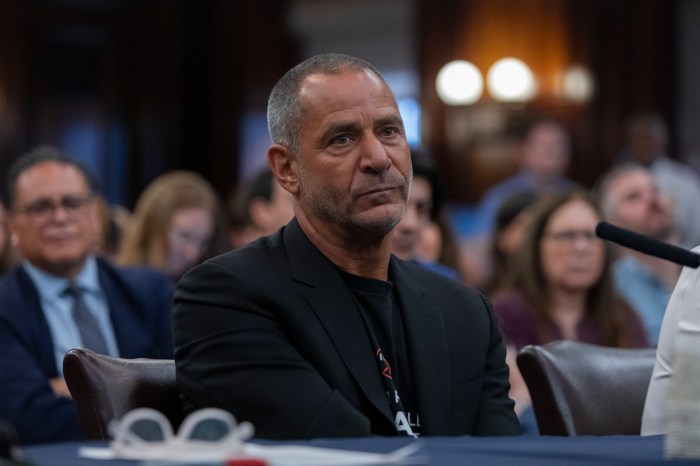

Leading the charge for the brokers was James Whelan, president of REBNY.

“Housing affordability will not be solved by this misguided and hollow legislation,” said Whelan. “Legislation that will make rents higher, further limit housing access and threaten the livelihood of hardworking agents is legislation that New York City elected officials should be unanimously against.”

While Gary Malin, chief operating officer for The Corcoran Group, agreed with Reynoso’s assertion that not enough housing is being built, he said the FARE Act would only make things worse.

“We all support a more affordable New York,” Malin said, according to Brooklyn Paper’s sister site amNewYork. “However, this bill will not achieve that goal. We face a supply and demand issue. Until we address this, pricing will not change. The market will become less negotiable. Landlords will become more rigid in the fees they charge, and these fees will be baked into the cost of rent, pushing them even higher.”

With the hearing complete and testimony collected, Julie Menin, chair of the committee on Consumer and Worker Protection, will next decide whether or not to bring the bill to a committee vote. If it passes, it will head to a vote before the whole City Council. The FARE Act has garnered at least 31 co-sponsors, just shy of the 34 needed for a veto-proof majority.