Flood-prevention infrastructure in the People’s Playground remains far from completion seven years after Superstorm Sandy devastated Coney Island, and what safeguards do exist won’t protect against a Sandy-sized storm — leaving residents vulnerable to flooding for years to come, according to advocates.

“We’re very, very lucky that we didn’t get hit by a hurricane this season,” said Brighton Beach resident and environmentalist, Ida Sanoff, who criticized the lack of substantial flood-prevention measures. “It’s very minimal.”

Since the superstorm struck the People’s Playground on Oct. 29, 2012, only a handful of initiatives included in a $2 billion resiliency investment have seen completion, such as the installation of back-up generators at public housing complexes, the installation of a tidal barrier at Coney Island Creek, and the relocation of Coney Island Hospital’s critical patient services to a non-flood zone, according to the Mayor’s Office of Resiliency.

Other projects, including the protection of subway yards to protect flooding, the construction of new sewer lines to improve stormwater management, and the installation of electrical lines and boilers to the roofs of public housing towers remain ongoing seven years after the storm.

“We’re still lacking a regional protection plan,” said Councilman Mark Treyger (D–Coney Island). “I believe that as a city, we’re better informed than we were prior to Sandy, but we’re not fully prepared yet.”

Major long-term mitigation efforts to defend against rising sea levels exist today as pipe dreams. The US Army Corp of Engineers proposed an ambitious multibillion-dollar, miles-long floodgate that would stretch from Jamaica Bay, through Coney Island, and out to New Jersey, but that project remains in the early design phase and is at best decades away from completion, according to a report by the Army Corps.

Other projects are closer to completion, such as the upcoming repairs to the bulkhead along Coney Island Creek that was damaged during Sandy, but those won’t be finished until 2023, and will only protect against small storms, not hurricanes the size of Sandy, according to representatives at the Economic Development Corporation, the agency in charge of the project.

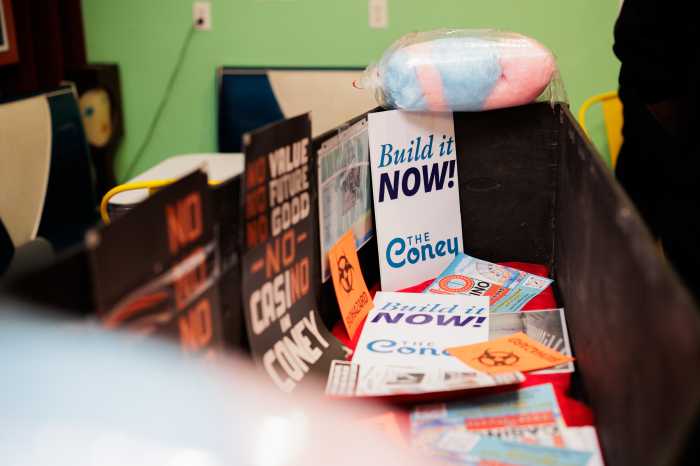

And as real solutions remain underfunded and behind schedule, locals are demanding the city fund stop-gab defenses that might provide some relief against future floods, such as planting more grass that prevents beach erosion, adding sand to the shoreline, and other natural fixes.

As things stand today, however, Coney Island is more-or-less as vulnerable to a Sandy-level storm as it was in 2012, when the storm caused roughly $19 billion in property damage in New York City and claimed 53 lives throughout the state, and locals are sick and tired of feeling like sitting ducks in their own homes.

“If a storm happened tomorrow, we’d still get flooded,” said Eddie Mark, the District Manager of Community Board 13, which oversees Sea Gate, Bensonhurst, Coney Island, and Brighton Beach. “The people are aware of what can happen, but they can only be as prepared as their go bag.”