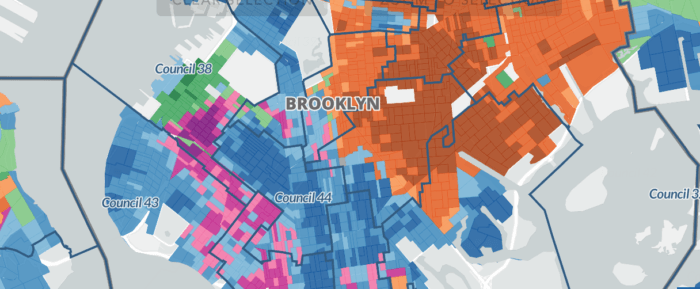

The future of a new majority-Asian New York City Council district spanning Bensonhurst, parts of Sunset Park, Bath Beach and Gravesend is uncertain after the city’s Redistricting Commission rejected a set of maps that included it on Sept. 22.

The fast-growing Asian community in southern Brooklyn has been pushing for a majority district for decades to connect areas where large numbers of Asian Americans are living and organize voting power to elect a representative that understands the community’s needs. This summer, the city’s Districting Commission — responsible for redrawing council districts to reflect the most recent U.S. Census — released a map that included one such district in a redrawn District 43.

“It is encouraging that the Commission mapmakers took seriously the mandate to keep communities as intact as possible while creating a district that gives voters the opportunity to elect candidates of their own choice,” said Don B. Lee, the board chair of Homecrest Community Services and spokesperson for the South Brooklyn Asian Coalition, in a statement.

‘We should be with our neighbors’: the case for a majority-Asian district

Community members had requested the commission draw two Asian-majority districts in southern Brooklyn but, so far, that has not come to fruition — the proposed maps included just the one.

There’s still a chance things will change — last week, the 15-member commission voted 8-7 to reject its own proposed map. If they had approved the map, it would have headed to the City Council for a vote. Instead, the committee will meet once again to “discuss next steps,” Gothamist reported.

“We had encouraged Commission staff to draw lines to create two Asian-American plurality districts in southern Brooklyn, but instead they opted to create one district in which the borough’s fast-growing Asian-American community comprises a majority,” Lee said. “We appreciate their listening to our concerns even if it did not do all we had hoped for.”

Though, Lee said they are happy that their main objective has been realized: drawing a district that includes a majority of Bensonhurst, which, for a long time, has been split between four council districts.

“The most important thing the proposed maps would accomplish is to keep Bensonhurst largely in one district so we can work with our neighbors on issues of common interest including affordable housing, responsible public and private developments, transportation infrastructure, support for small businesses, immigration and safe streets,” Lee said.

The coalition would have preferred the commission kept neighborhoods intact instead of drawing a large district based on racial lines, Lee said, as they want to be a part of their communities where they can support one another instead of being separate from their neighbors but believe they must fight for equal representation.

“A lot of folks choose to be in Bensonhurst, Brooklyn. We should be with our neighbors,” Lee said. “We want to ensure proper representation, whether Asian or not Asian but we have to represent each other.”

The well-organized advocacy of southern Brooklyn’s Asian population was further buoyed by the federal Voting Rights Act, which forbids the redistricting process from being used discriminately against racial minorities, and requires drawing districts along racial lines to promote minority communities’ ability to vote for a representative of their choice.

“The Voting Rights Act forbids the diluting of racial language minority groups,” said Dan Kaminsky, good government group Citizens Union’s public policy and program manager. “And so the commission has done an analysis that has found, and it’s not a surprise, there is racially polarized voting in New York City, meaning different racial groups will for different candidates, often along racial lines.”

“Because of that, you have to draw districts in a way that allows minority groups to [have] the ability to elect a candidate of their choice,” he added.

More than 100,000 people, or 44% of the population, in the proposed District 43 identify as Asian, according to the city’s Department of City Planning. The neighborhoods that make up the district — Bensonhurst, parts of Bath Beach, Sunset Park, and Gravesend — currently sit in districts 43, 44 and 47, which each have a large plurality of Asian residents that have been growing by huge percentages since the 2010 US Census, reporting increases of their Asian population by nearly 48 percent, 52 percent and 35 percent respectively.

Kaminsky described the demographic statistics and City Council district lines as “mismatched” and a “strong argument” for creating an Asian-majority district.

“The last [district] lines are set cuts the neighborhoods up in such a way that Asian Americans do not have the ability or are not a plurality and therefore are potentially denied an opportunity to elect a candidate of their choice,” Kaminsky told Brooklyn Paper.

Despite the redistricting commission voting against the Sept. 22 maps, Kaminsky projects the proposed District 43 will remain largely intact as it wasn’t discussed by any of the dissenting commissioners in addition to the legal requirement posed as part of the Voting Rights Act.

“If you look at the things that those eight [dissenting commissioners] said, nobody really brought up complaints against that specific district,” Kaminsky said, “And sort of with the federal context in the Voting Rights Act, I wouldn’t be surprised if they and because it’s in both the preliminary and the revised, I don’t see specifically, that district being touched.”

Political pressure and next steps

It’s also not the district within the proposal that drew ire from Mayor Eric Adams, who selected seven commissioners on the redistricting committee. Politico recently reported the commissioners were pressured by a top aide to the mayor to reject the draft maps.

Politico credited the pressure from City Hall to the chopping up of District 47, represented by moderate Democratic councilmember Ari Kagan, who aligns politically with the mayor. Initial proposals would have pitted more progressive councilmembers Justin Brannan and Alexa Avilés against each other in a primary race — Brannan who fell out of favor with the former Brooklyn Borough President during last year’s Council Speaker’s race.

But the map rejected on Sept. 22 had separated Avilés and Brannan’s districts, giving them an easier path to victory, and left Kagan in a more precarious position.

Regardless of the fallout from the alleged controversy, Kaminsky does not expect it to have an effect on the newly proposed District 43.

“He was more interested in having that shakeup happening in southern Brooklyn and that is one of the reason he pressure his commissioner to vote no,” Kaminsky said. “That still, I don’t think, would necessarily affect the southern Brooklyn Asian district.”

The Districting Commission will be hosting meetings on Sept. 29 and 30 to redraw the maps to meet the concerns of the commissioners who voted no last week. A follow-up vote is scheduled for Oct. 6. Nine of the 15 commissioners need to vote for the map for it to pass.

If approved, the maps will be sent to City Council who have three weeks to deny, approve or take no action. If the City Council approves or takes no action, the process is over, and the new district lines are official.

If the City Council denies the proposal it goes back to the districting commission, who will then redraw the district lines with consideration of the City Council’s concerns. Following the public hearing or hearings, the maps will be redrawn with consideration of citizen feedback and presented to the commission for one final vote.

“This time it’s approving the maps, not approving sending them to City Council. If it goes back to the commission, it does not need to go back to City Council. The commission has final authority over the maps so long as nine out of 15 commissioners vote to approve the maps,” Kaminsky said. “ And from a structural standpoint, we really liked that, because we don’t think it should be elected officials who have final authority on the line they have to run, it should be folks, at least a step or two or degree away from that.”

The finalized maps are due to the New York City Clerk by the Dec. 7 deadline, which has been pushed up because of the city’s new voting schedule — the council primaries will take place in June.

There are still ways to express your thoughts on the redistricting process despite the citizen engagement period having passed. Email written testimony to testimony@redistricting.nyc.gov, or reach out to your city councilmember once the commission sends them the maps.

Editor’s Note: Brooklyn Paper’s publisher, Josh Schneps, is a member of the Redistricting Commission.