The Environmental Protection Agency has declared the fetid Gowanus Canal a federal Superfund site.

The controversial designation, announced on Tuesday, sets into motion a half-billion-dollar, decade-long, federally overseen clean-up of the polluted waterway, which cuts a sclerotic artery through the gentrifying heart of Brownstone Brooklyn. But it also raises questions about whether developers, who currently yearn to build residential housing in the canal zone, will ever exhibit quite the same ardor now that the area has been deemed one of the most polluted places in the country.

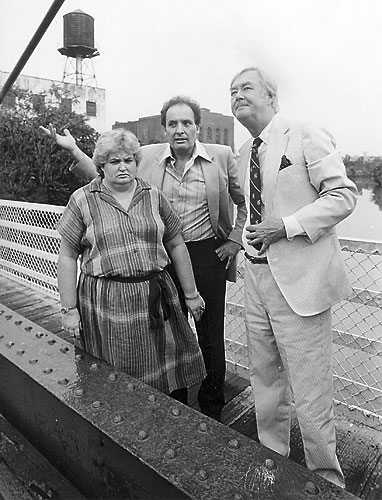

“This site has a very long legacy of toxic pollution,” said Judith Enck, the EPA’s regional director. “And because of that, the EPA is saying it is adding the Gowanus Canal to the federal Superfund list. We believe it will get us the most efficient and comprehensive clean-up of this waterway.”

Enck started her statement by declaring that taxpayers should rest easy that the feds went with a Superfund designation, which seeks restitution from responsible polluters.

“The goal of Superfund is to ensure that polluters pay for clean-up, not the taxpayer,” she said.

Along the canal, however, EPA has identified nine responsible parties, including National Grid, Con Ed, several petroleum companies, the U.S. Navy and the city of New York.

As a result of the city and Navy involvement, taxpayers will be partly responsible for the clean-up.

Enck defended the Superfund method because it puts a legal requirement that polluters pay.

“If the Navy and the city have polluted, they have a legal obligation to pay,” she said.

Both National Grid and Con Ed pledged to cooperate fully with the clean-up, which Enck said would take “10 to 12 years.

“That’s perhaps not fast enough for some, but it took many, many decades for this pollution to occur, so give us a decade,” she said.

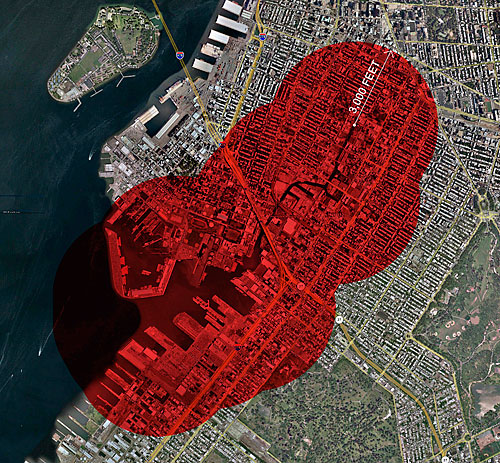

There are limits to what a Superfund designation can accomplish along the 1.8-mile canal, which runs from Butler Street to Gowanus Bay.

Only a portion of the canal bed — where a thick muck of chemicals lies undisturbed — is expected to be dredged, though EPA’s regional Superfund administrator Walter Mugdan said that further investigation could indicate that the entire canal must be dredged.

And the EPA’s clean-up would not cure the canal’s most malodorous problem: the millions of gallons of raw sewage that flow into it during heavy rainstorms, a remnant of the city’s antiquated sewer systems. He did say that the city and state are already working on the multi-billion problem, and that EPA would monitor their success.

“If there is any ongoing [toxic] pollution entering the canal, those sources have to be shut off and eliminated,” he said, mentioning that there are 214 pipes that empty unidentified material into the canal. “We don’t want to clean up the mud only to have it be recontaminated. If there are toxic chemicals, we will track back and make sure that they are stopped.”

Under questioning from reporters, Enck explained how the agency came up with the 10- to 12-year timeline — and the $300- to $500-million expected cost.

By the end of this year, the agency will complete a “remediation investigation and human-risk assessment,” she said.

After that, it will take another year to complete a “feasibility study to examine clean-up options,” she said.

By the end of 2012, the agency will select a remedy plan. Then, by the end of 2014, that plan is designed.

It would be implemented over the next five years, she added — “and we’ve added two years [more] as contingency.”

“I wish [the clean-up could be completed] sooner, but this is a complicated site,” Enck added. “We will move as quickly as we can, but we need to be honest with the public.”

Mugdan explained that there are serious questions about how best to remedy the situation.

“There are questions about how deep we should dredge,” he said. “Do you then back-fill with clean material? How do you deal with crumbling bulkheads along the canal. [What about] ongoing groundwater migration? These are technically difficult questions that we will be answering.”

The canal has been a polluted wasteland for more than a century — and talk of cleaning it up are nearly as old. But the process was jumpstarted last April, when the EPA announced that it was considering adding the canal to the so-called National Priorities List.

Around the same time, Mayor Bloomberg declared himself an opponent of Superfund designation, claiming that he had a better, faster and cheaper plan to clean the waterway using existing federal programs, such as the Water Resources Development Act, which would involve the Army Corps of Engineers. Opponents derided the mayor’s effort as too little, too late — and too underfunded, because such a clean-up would require annual budget allocations from the federal government.

Enck specifically addressed that in her statement on Tuesday, claiming that the Water Resources Development Act has an annual budget of roughly $50 million.

“And that’s for the entire country,” Enck said. “Clearly, that was not enough money. … I was not relishing going to Congress every year to get funding.”

Hours after Enck’s announcement, Mayor Bloomberg issued a statement pledging his begrudging support.

“It’s disappointing,” mayoral spokesman Marc LaVorgna said in an e-mail. “We had an innovative and comprehensive approach that was a faster route to a Superfund-level clean-up and would have avoided the issues associated with a Superfund listing. The project will now move on a Superfund timeline, but we are going to work closely with the EPA because we share the same goal — a clean canal. Local residents and businesses raised concerns about the impact of a Superfund designation on their community and we hope that the EPA will work with us to address those concerns as they move forward.”

Other local pols rejoiced in the news.

“[Superfund] is simply the most reliable way to ensure we have the dollars and the coordination to undo years of environmental damage,” said state Sen. Daniel Squadron (D-Brooklyn Heights).

But Superfund critics point to the political reality in the mostly industrial canal zone, which the mayor wants to rezone into a mixed-use community of manufacturers side-by-side with thousands of new residential units. One key development company, Toll Brothers, envisions a 450-unit canal-side complex with a waterfront esplanade.

But the company publicly announced last year that the project is dead in the water if EPA went ahead with a Superfund designation.

Sure enough, Toll Brothers followed through on its promise.

“We are very disappointed with the ruling and in light of it will not be proceeding with our project,” said David Von Spreckelsen, a spokesman for the developer.

Some locals echoed the company’s frustration.

“God help us!” said Buddy Scotto, a Superfund opponent and longtime Carroll Gardens environmental and housing activist. “I’m disappointed. The private sector was willing to spend $450 million on affordable and senior citizen housing that we desperately need.”

Scotto added that he was wary of the timeline put forth by the feds.

“The federal government is committed all over the country. … God knows when they’ll get around to us.”

But not all developers were so dismayed.

The Hudson Companies, which has its own plan for mixed-income housing and open space along the canal, was not deterred by the Superfund listing.

“Though the listing presents new challenges for the financing and construction of the project,” the company said in a press release, “we remain eager to work collaboratively … to overcome these obstacles and develop as planned.”

The Superfund program’s track record is somewhat spotty. Numerous clean-ups took decades longer than originally promised and cost far more than originally budgeted. But other sites were cleaned successfully after decades of neglect.

And the term “Superfund” is a bit of misnomer. Despite its name, the Superfund is not a pool of money that federal officials tap into for environmental remediation. In fact, one goal of Superfund designation is to identify guilty polluters and get them to pay to clean up toxic sites.

Enck denied that a Superfund clean-up has a stigma that is insurmountable.

“I’ve heard that people say there is a ‘Superfund’ stigma, but there already is a stigma,” she said. “Everyone in Brooklyn knows that the Gowanus is heavily contaminated. … When the site is remediated, there will be even more development opportunities.”

In the end, she likened the Gowanus Canal to the Hudson River before it was declared a Superfund site two decades ago.

“Back then, no one would have lived on the banks of the Hudson,” she said. “But we made a massive commitment and now people flock to recreate and live on the shoreline — in luxury apartments that I certainly can’t afford.”