Gov. Kathy Hochul gave new life to a proposed statewide ban on gas hookups in new buildings on Jan. 5, and now two local legislators are pushing to include the idea in this year’s state budget.

State Sen. Brian Kavanagh, who represents parts of lower Manhattan and the Brooklyn waterfront, along with Assemblymember Emily Gallagher, who represents parts of northern Brooklyn, introduced the “All Electric Building Act” last year, which would ban municipalities from issuing gasoline permits to all new buildings by the end of 2023.

That bill is now going working its way through the committee process in both chambers, and has a ways to go before landing on the governor’s desk — but Kavanagh and Gallagher are calling on Hochul to match her words with action and speed up the implementation of the policy by including it in the executive budget, which is due on January 18.

The renewed push for cleaner energy in homes statewide comes on the heels of a New York City Council vote to ban new gas hookups in smaller buildings in 2024, and in larger ones starting in 2027.

The governor indicated during her first State of the State address last week that she would pursue such a policy, and ban new gas hookups statewide by 2027, while also amending building codes to incorporate the reduction in greenhouse gas emissions required by the state Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act (CLCPA.)

She also pledged to create at least 1 million all-electric homes in the state by 2030.

“These are huge breakthroughs in loosening the death grip of burning carbon on our lives, our communities, and our future,” Gallagher said at a press conference on Tuesday morning. “But the timeline that they each laid out fails to meet the reality of the climate crisis.”

Instead of Hochul’s 2027 target, Gallagher and Kavanagh said their 2023 goal was necessary to meet the scale of the climate crisis. Including the All Electric Building Act in this year’s budget would implement the law’s more immediate deadlines as soon as the the financial plan is approved.

In 2018, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change said that human carbon emissions need to be reduced by 50 percent by 2030 to make an impact on the increasingly hard-felt effects of climate change, and Gallagher lamented the lack of progress on the issue over the past four years.

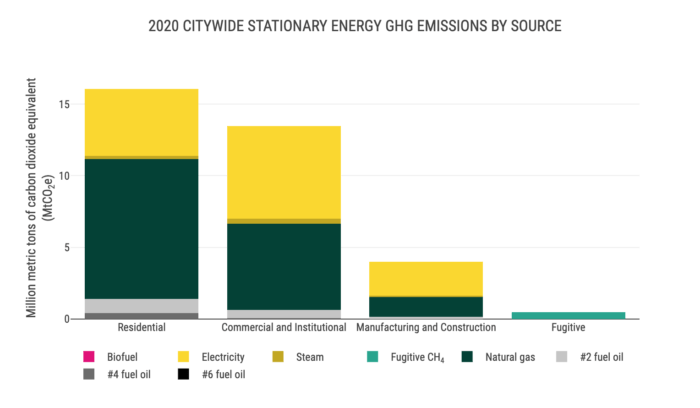

“Now 12 years is down to eight,” she said. “Buildings account for one-third of New York’s greenhouse gas emissions. There is no path for meeting our state’s climate goals without tackling this industry.”

Getting the legislation signed as part of the budget would allow lawmakers to get to work on the nuances of implementing it in real life before it goes into effect next year, Kavanagh said. It would also reduce the chances of the bill languishing in Albany until the end of the legislative session in June.

The law does have some allowances for buildings with absolutely no option but to use fossil fuels after 2023, according to Kavanagh, but the technology for all-electric construction is “readily available” — and, once the bill is passed, the state would be engaging in a study to make sure it would not be increasing the cost of housing and energy for low-income New Yorkers.

Heat pumps and other electric means of providing heat and power are readily available and largely up-to-snuff, he said, which is why lawmakers are pushing for such tight deadlines.

Carbon dioxide in New York State

While vehicles and power plants are the most-discussed producers of greenhouse gases, construction and the everyday use of natural gas for cooking and heating buildings produces more than half of New York City’s annual emissions.

In November, the council of Ithaca, an upstate city of about 30,000 people, voted to electrify all of its more than 6,000 buildings by 2030.

Sonal Jessel, the director of policy at WE ACT for Environmental Justice, said that changing policies around new construction is the easiest way to get started tackling climate change in a tangible way — and she anticipates the utility bills for people living in these all-electric buildings would be significantly lower than they are for people paying for natural gas.

New York’s alternative energy providers are ready to meet the challenge, said Bill Nowack, executive director of the New York Geothermal Energy Organization — and, as more and more of the state’s infrastructure is moved away from fossil fuels, costs for the remaining gas customers will increase.

“We do not want to set up our low and moderate income communities to be the ones paying this off,” he said. “There should be no new [low and moderate income] buildings going up with fossil fuel heating in New York State at this point.”

Nowack argued that the state should stop subsidizing natural gas, ending a policy of providing free pipes to new buildings who are seeking gas hookups and implementing a geothermal tax credit like the one already in place for buildings utilizing solar energy.

The all-important heat pump, which runs on electricity and works by pulling the warmth out of the air outside and routing it in, even on the coldest days, said Pete Sikora, a campaign director with New York Communities for Change, and the technology has improved enough to stand up to the chilliest New York winters.

In addition, installing all-electric infrastructure is generally about the same cost as installing the traditional, fossil-fuel reliant heating and cooking infrastructure.

“The proof’s in the pudding, there’s lots and lots of developers all over New York City building buildings that are all-electric,” he told Brooklyn Paper.

New York’s grid is hardy enough to handle new construction relying exclusively on electricity, he said, but will need to be shored up and, preferably, connected more extensively to renewables, before large numbers of older buildings can be converted away from natural gas.

Sikora also emphasized that using “clean” sources of heat and energy are still important, even if they’re using electricity generated by fossil fuels.

“If you plug in a car on the New York City grid, which is dominated by fossil fuels, and you charge it, you’re charging it off a dirty grid, which is powered by fossil fuels,” he said. “However, you’re producing much less pollution than if you ran a car with a gasoline-powered engine.”

By the same measure, he said, a heat pump, while it may be plugged into the “dirty grid,” is still doing less damage, and, year over year, New York’s grid will get cleaner, making the all-electric buildings even more environmentally friendly.

Daphne Rose Sanchez, the executive director of Kinetic Communities and a resident of Greenpoint’s Cooper Park Houses, noted that electrification would have benefits far beyond the climate — as gas hookups can lead to health problems, particularly for lower-income residents.

“This particular bill is a very important bill because a lot of community members tend to seek homeownership, they tend to seek an opportunity to live in a better, safer, cleaner environment,” she said. “However, time and time again, when there is new construction, it’s the cheapest route possible in order to get the building erected.”

As a result of the cost-cutting, low-income communities and people of color suffer in unsafe, high-emissions buildings, she argued.

All-electric buildings reduce the safety and health hazards of gas stoves and boilers or furnaces, and should be accompanied by stricter building codes to avoid tragedies like last week’s deadly fire in the Bronx, Sanchez continued.

Brownsville resident Rachel Rivera — whose ceiling collapsed during Superstorm Sandy despite her home being outside the most at-risk zones, causing her to lose her pets and her valuables — echoed Sanchez’s arguments, noting that lower-income, minority communities are often the hardest hit by the extreme weather brought on by climate change.

“We’ve lost way too many lives in New York,” she said. “We need to start doing something now, because waiting for 2027 is too late. The faster the better, because it’s just getting worse out there, and I don’t see a future out there if we wait any longer for my kids or for even my grandkids. We need to move now and start moving faster.”