To tree, or not to tree? That is the question at the center of the third lawsuit targeting the city’s long-planned overhaul of Fort Greene Park.

The lush but aging greenspace was chosen as one of eight city parks to be overhauled by the Parks Without Borders program in 2016. Nine years later, the projects have wrapped up in the other seven parks — but haven’t begun at Fort Greene.

That’s because a group of local activists, the Friends of Fort Greene Park, believe the project will do more harm than good, and doubt the city’s studies that say otherwise. In an effort to stall the project and demand more information about the plan, the Friends have filed three lawsuits against the city since 2018.

The crux of their concerns lie with the parks department’s plan to remove 78 trees as part of the redesign.

Late last month, the court heard oral arguments in the most recent suit, which was filed in 2023. In it, the Friends claim the city failed to properly assess the potential negative environmental impacts of the project and that going forward with it would violate their rights under the state constitution’s Green Amendment.

Verice Weatherspoon, a member of FFGP, said she has lived across the street from the park for decades.

“The trees being cut down affects the environment, you get more healthy, clean air with more trees and more greenery,” she said. “I don’t understand why the city wants to destroy that and take down trees.”

But the city — and the Fort Greene Park Conservancy, the nonprofit organization that works to maintain the park and run events — disagree. Those in support of the project say the lawsuits have held it up unnecessarily, and that the delays have prevented other unrelated improvements from moving forward.

Fort Greene’s supporters are split

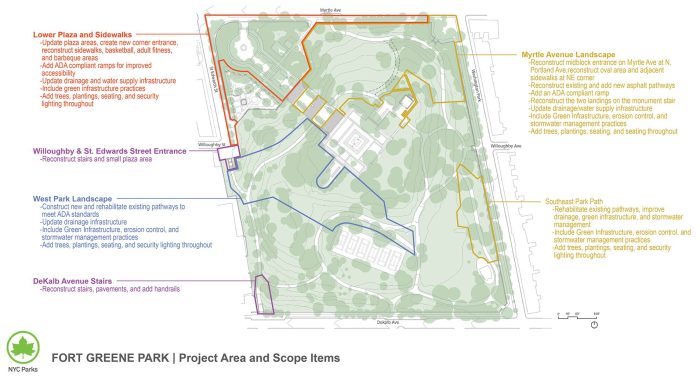

The $24 million project in question — which has been revised and expanded since its first iteration in 2017 — includes new ADA-accessible entryways and new sidewalks along Myrtle Avenue; new and reconstructed pathways; more lighting and benches; and infrastructure to control flooding and flood damage.

Much of the park is under-lit, said Rosamond Fletcher, executive director of the Fort Greene Park Conservancy, and parts are inaccessible for people using mobility devices or strollers. Fort Greene Park is especially hilly and prone to flood damage — in several areas, the Conservancy has installed wooden railroad ties and anti-erosion netting to keep soil in place.

“I understand people don’t like to hear that trees are coming out, and as a conservancy, we typically are not in favor of that,” she said. “But we have to look at the whole project, the amazing opportunity it presents to address accessibility in the park, and the park’s long-term environmental health.”

The Friends of Fort Greene Park are largely in favor of some improvements, several members told Brooklyn Paper ahead of oral arguments last month.

“On Myrtle Avenue right in front of the park, the sidewalks are very uneven … and the pathways are not that good,” Weatherspoon said. “Surrounding the park, on St. Edward’s Street, there are stairs leading up to the park, and the stairs are just so crumbly, it’s hard to maneuver, especially for senior citizens, kids.”

Their main point of contention lies in the park’s northwest corner, near the corner of Myrtle Avenue and St. Edward Street. The city wants to construct a new entrance there, reconstruct the barbeque area, basketball courts, and fitness center, and level the infamous “mounds” at the foot of the park’s massive stairs to create a wide plaza.

To do that, it would have to chop down dozens of trees — many of the 78 set to be removed as part of the park’s revamp.

The Friends say that would hurt the park and the locals who frequent it, especially residents of Ingersoll and Walt Whitman Houses directly across the street.

In the suit, they claim cutting down trees would “result in adverse impacts to air quality in a known asthma neighborhood cluster,” and would make that corner of the park hotter, louder, and less hospitable — which they say could push locals to use it less often. The lawsuit also claims the city’s Environmental Assessment Statement, which found no significant impacts associated with the project, is not sufficient.

Enid Braun, a founder of the Friends of Fort Greene Park, said in a statement she hopes the lawsuit “will force the City to explain the lack of planning, environmental review and a distinct lack of transparency.”

The city had, initially, declined to do an EAS, having classified the project as a “minor” action exempt from environmental review. In 2020, in response to another lawsuit filed by the Friends, a judge ordered the city to prove the project wouldn’t have a negative environmental impact.

In response, the parks department expanded the project to include improvements on the west lawn and conducted the EAS, which concluded that while the project might have temporary impacts on the park ecosystem, they would be just that: temporary.

“When a city agency goes through, does a proper environmental review, there’s not really much the judge can do,” Fletcher said.

The trees on the chopping block

More than 200 trees will be replanted in and around Fort Greene Park to replace the 78 removed. Most would be larger and more developed than the small, fragile saplings that typically appear in tree pits, Fletcher said.

Of the 78 trees chosen to be removed, 30 are “condition-based,” per city records — meaning they’re sick, poorly-planted, or otherwise destined for a short life. The other 48 are being removed for design purposes. Most are full-grown, healthy trees, including a cluster of Honey locusts at the corner of Myrtle Avenue and four London plane trees at the edges of the future plaza.

Half of the 48 trees being cut down for design purposes are invasive Norway maples. Though the trees are pretty, their thick canopies prevent sunlight from reaching low-lying plants on the ground and prevent anything from growing there. Many of the Norway maples in Fort Greene Park are surrounded by bare dirt, which is particularly vulnerable to erosion.

Several Zelkova trees will be removed from the landing on the park stairs. Though those trees are technically healthy, they were planted too close together, and their long roots “wreak havoc on the drainage system,” Fletcher said.

Pain over the plaza

The lawsuits and the continued delay of the Parks Without Borders project has had a knock-on effect on other projects, Fletcher said, because they can’t explore other capital improvements with one still in the works. The park needs new bathrooms, she said, but they can’t seek funding for them yet, and the Conservancy has also had to pause a professional tree care program.

But members of the Friends want the city to forget about the plaza and move forward with other elements of the project. The group has put forward alternative proposals, but say officials have not entertained them.

“They’re holding basic repairs hostage,” said member Kelly Schaffer. “Then they claim that we’re holding up repairs … it’s like, they’re holding up repairs that have nothing to do with this thing. Like, maintaining all these other paths, why is that related to building a plaza or not?”

Schaffer worries the plaza would only be used for Parks Department-approved events, not for community use.

Fletcher said the park’s typical events — the Greenmarket and the Artisan’s Bazaar — will stay in their traditional spots, and will not relocate to the plaza.

During oral arguments, Judge Ariel Chesler remarked that the city and the Friends of Fort Greene Park aren’t so far apart — except on the trees, said Peter Engel, a FFGP member. A decision is likely to take about 60 days.

Meanwhile, Fletcher said, the project is in procurement — the city is seeking contractors to carry out design and construction, and work is expected to start early next year — unless there are further delays.

The Parks Department declined to comment, citing pending litigation.