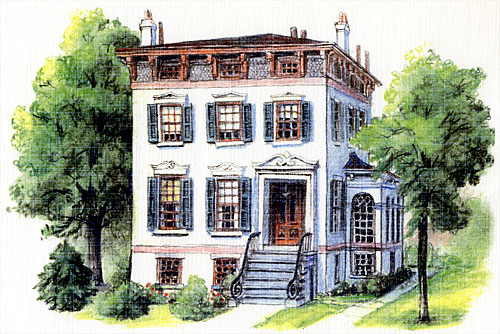

A plan to tear down 10 historic houses at the Brooklyn Navy Yard and replace them with a supermarket has been delayed indefinitely thanks to a decision by federal officials to review whether the dilapidated 150-year-old mansions can be saved.

“There is absolutely no way we can give any sort of end date at all … there is no mandated time limit,” said Kristin Leahy, the manager of the National Guard Bureau Cultural Resources Program, which is investigating the mansions’ historical integrity — to the frustration of those eager to see the run-down buildings torn down.

Leahy said the earliest that she could hold a meeting with the city, area residents and preservationists is March. And that meeting would be just the first of a series.

Admirals Row, which overlooks Flushing Avenue near Navy Street, sits on six acres of federally owned land in the otherwise city-controlled Navy Yard.

The National Guard wants to sell the land, and according to local law, must give the city first dibs. But because of the houses’ historic significance, the Guard must also go through an arduous public comment and historic review process.

“I’m disappointed,” said Councilwoman Letitia James (D–Fort Greene), a proponent of the supermarket proposal.

“We’re trying to expedite the process,” added James. “[And] we’ve been in touch with some federal elected officials [to help do that].”

The Navy Yard’s proposal is popular in the surrounding community, particularly among residents of the Farragut, Ingersoll and Whitman public housing projects, who have little access to fresh produce.

“Saving historic homes may be significant to some people, but to the people who live in a neighborhood that doesn’t have easy access to fresh fruits and vegetables, it is of much less importance,” Ed Brown, the president of the Ingersoll Tenants Association, recently said in a letter to The Brooklyn Paper.

Even so, neighboring and city preservationists argue that the houses should be rehabilitated, and are pleased that the federal government is taking its responsibilities seriously.

“I think they’ve handled themselves well,” said Scott Witter, a Clinton Hill artist and one of the most outspoken opponents of the city’s plans.

Simeon Bankoff, another opponent of the city’s plan and the executive director of the Historic Districts Council, agreed, saying that the National Guard’s deliberate approach has convinced him that there would not be “a rush to judgment.”.