When the doors opened for eight of Brooklyn’s school districts last September, parents and teachers walked into three new literacy curricula that the Department of Education unveiled in May 2023.

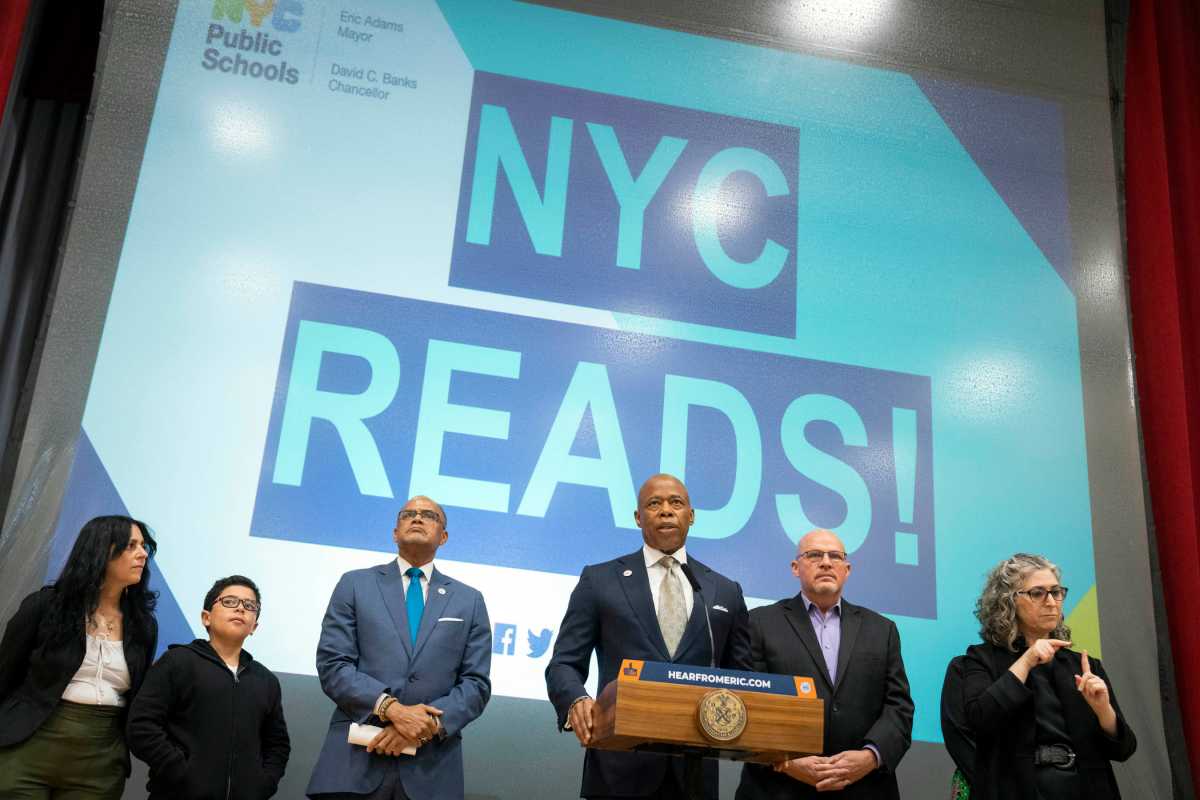

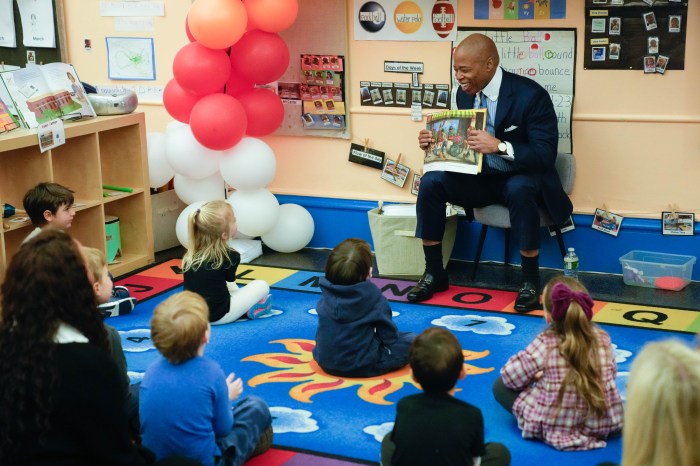

The new program, “New York City Reads,” announced by Mayor Eric Adams and Schools Chancellor David C. Banks, were part of a larger effort to improve the reading levels across New York City’s public schools, which have been below average for many years.

Within months, however, parents, teachers, and even students became dismayed with the programs. Some claimed that new textbooks had no emphasis on critical thinking — many of them consisting of simply passages — while others said the new literature was not culturally responsive in a multicultural city.

Heather Trovato, a mother of two from District 22, said both of her children are struggling with their new curricula, including her youngest who attends elementary school. She feels her kids would better learn from the formerly-used Teacher’s College approach, which city officials claim “has not worked.”

“I can accept the fact that my own particular kid would have been better off under the old approach,” she told Brooklyn Paper. “[But] I feel sad about some of the changes because I feel like my kid was a lot more interested in going to school and in reading before.”

Andrea Castellanos, who teaches in school district 23, which encompasses Ocean Hill and parts of Brownsville, said the reading curriculum is not deep enough for her students.

“There’s this very superficial coverage of content,” she said, adding that the topics are often about science or social studies. “And the kids might have a superficial understanding of it. You read three books, you did some literacy skills. You wrote an opinion essay, what did you really learn about this? It’s not deep learning. And the curriculum that we are given doesn’t always know our students the way that we do.”

These issues about the literacy curriculum mandate reflect the ongoing difficulties with reading levels among public school students in New York City and Brooklyn, a problem that has persisted citywide for many years.

Fighting for literacy

Reading levels have been low across the city for at least the last 25 years, according to the New York Times. In 2003, federal tests showed that 22% of eighth-grade New Yorkers were proficient. That number dropped to 19% in 2005.

In September 2007, eighth-grade reading levels were lower than in 1998. As of June 2009, reading proficiency for fourth graders had plateaued, while eighth graders continued to fall behind, according to federal exam results.

However, that same year, state test scores showed nearly 70% were up to par — but then, former Chancellor of the Board of Regents Merryl Tisch announced that the scores were inflated. Earlier this year, Gothamist reported that preliminary screener data showed the same recurring statistics. As of the winter of 2022, two-thirds of public school students were not proficient in reading.

Last May, Adams and Banks announced the new reading curricula. Banks referred to the changes as “the beginning of a massive turnaround.” Perhaps the biggest change was the slow fadeout of the Teacher’s College reading curriculum, something a few hundred elementary schools used as of 2019 and many teachers were trained on.

The changes were to occur in two phases for all school districts. For Brooklyn, Phase 1 happened for the 2023-2024 school year with Districts 14, 16, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, and 32. The other districts, 13, 15, 17, and 18, will go through Phase 2 starting this September. Elementary schools are required to take part in this new curriculum, while middle and high schools at this point are not, though superintendents are allowed to make that opt-in themselves.

The city also offered three textbooks for superintendents to choose from: Wit & Wisdom, Expeditionary Learning, and Into Reading — often known as HMH because of its publisher, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. HMH appears to have drawn the most criticism among Brooklynites in Phase 1.

Dissatisfaction spreads

Martina Meijer, who teaches at a District 22 elementary school, is one of those Brooklynites against HMH.

She explained that her students must complete “rigorous” online assessments for every module they finish. The problem, she said, is not every student is a skilled typist, which makes and some struggle through the online assessments. At the same time, Meijer said there is a noticeable lack of enthusiasm among her students for reading.

“They all have to read the same book at the same time,” she said. “It’s never a real book, it’s only excerpts. They used to be able to read any book of their choice.”

“When we reviewed the curriculum [last] year, I voiced concerns,” she explained in a message to her local representative and Community Education Council 20 that she shared with Brooklyn Paper. “It appeared to be hyped up state test prep.”

“My son is in seventh grade and reads at and above grade level,” Garcia said. “However, he was struggling and failed his first couple of exams. I reached out to the teacher for support, but it seems like this curriculum provides little teaching and guidance aside from just doing these boring and redundant reading excerpts … I keep hearing how this format of excerpt reading is more in keeping with how we take in information in real life.”

After not getting a response, or any support from the City Council or her CEC, Garcia said she eventually hired an English Language Arts tutor for her son.

Brooklyn School of Inquiry, a citywide Gifted & Talented school in District 20, has also pivoted to the new curriculum.

Despite having a 90% reading proficiency level, BIS started using the citywide curriculum and the HMH textbook. Members of the school’s community said resentment built up among the students, teachers and parents, with several of them speaking out during a Panel for Educational Policy meeting in March.

One student, Carlo Murray, compared the lessons to test preparations. He also said he and his classmates used to love reading, but they now hate it.

During an April CEC20 meeting, another BSI student, Katherine Zhang, denounced the new program.

“I used to devote more of my attention to ELA,” she said. “But now, I don’t need to because it doesn’t capture my attention and we do the same thing over and over.”

Trovato’s eldest child also attends the school, and Trovato spoke up at the April CEC20 meeting. She explained that, while she understands some districts with a long history of low reading levels would need major changes, she doesn’t think high performing schools like BSI should have had to make the switch.

“Why fix what’s not broken?” she asked.

How to teach students to read

When asked about the backlash to the new curriculum, Nicole Brownstein, Director of Media Relations at the New York City Department of Education, said that structured literacy allows all children the skills to read, and promotes confidence. Meanwhile, balanced literacy, or the balance of language and phonics — part of older curriculums — may not work well for children who have difficulty reading.

“An approach grounded in the science of reading is universally designed to be good for all readers,” Brownstein said in a statement. “Thinking about it from a child’s perspective, they very much enjoy decodable texts and other phonics-based instruction because when they pick up the book and they have the tools to be able to read it, they feel much more confident. Encouraging practice helps build the child’s fluency, leading to greater comprehension.”

The conflict over the new curriculum does not surprise former CEC20 president Adele Doyle. An advocate whose doctorate studies focused on literacy, Doyle has been speaking out about reading comprehension in New York City for years, and several years ago traveled to Albany to make her case to state representatives.

Doyle maintains treating an entire population together instead of breaking down demographics is a disservice because “one size does not fit all.” She added that education has gone through several theories and experiments during the last 20 years — in turn, messing with the students, teachers and parents who are forced to keep up.

“Look what happened with the last curriculum,” Doyle said. “It didn’t work. And No Child Left Behind! They said that was a bipartisan response, and we’re going to have everybody reading at grade level by 2014. And they pumped $8 billion into that. And they quietly snuck away from it in 2014. Because not only weren’t they reading at grade level, less students were reading at grade level.”

Only time will tell if these new curricula will yield any results, Doyle said.

Preparing for Phase 2

While nearly half of the districts in Brooklyn are adjusting to or even struggle with the new curricula, the other half are preparing for their turn as Phase 2 approaches for the coming school year. The Presidents of CEC15 and CEC17 said they have been watching and communicating with those in Phase 1.

Erika Kendall, president of CEC17, said the Council was concerned when they reviewed all three textbooks and noticed they may not be a good fit for the diverse district.

“They simply weren’t culturally relevant enough for our community, and some of them didn’t have accessible or robust enough resources for parents to be able to support from home,” Kendall told Brooklyn Paper.

Seeing the BSI students at the PEP meeting to express their outrage only added to her concerns. Until there is a solution, she said CEC17 is working to make sure local libraries reflect the people of the district.

Last May, during the announcement of the new curricula, the Mayor’s Office said the DOE “will offer New York City-created, ELA-specific resources under the ‘Hidden Voices’ initiative,” which will tell the stories of those often left out of history books.

CEC15 president Antonia Ferraro Martinelli said there is a “wait and see” mentality as parents echo the concerns of their counterparts in District 20 — including about the one-size-fits-all approach when some schools already have good reading programs.

“It is difficult to ascertain whether the view reflects the majority of parents,” she said. “There have been requests for data demonstrating the effectiveness of these new curriculums. And of course, there are families who are supportive of a more prescriptive, structured reading curriculum, particularly as we see students struggle to read, spell, write complete sentences, and compose detailed paragraphs.”

When asked what advice she would give to the Phase 2 teachers, Castellanos said she’s found creative ways to still engage her students while using the curriculum. “I would encourage [others] to do the same.”

Brownstein said the DOE agrees there is “no one size fits all approach for any instruction.”

She said teachers know their classrooms, and can ensure each student is learning in a way that suits them.

“We trust our educators to know their students best and to adjust instruction so that every student is supported in their learning,” she said. “Small group instruction is one way that teachers are able to provide targeted support.”

Looking ahead

It’s also too early to measure the program’s success, Brownstein said.

“But anecdotally we are hearing from educators that their students are feeling more confident about their reading abilities,” she told Brooklyn Paper “Other states that have undertaken this effort have shared that this shift took years to demonstrate results. Mississippi, for example, took at least six years to see real results.”

Still, teachers worry about their students’ reading skills, given the program’s apparently rocky start.

“I don’t see any change, except for less differentiation and reading,” Meijer said. “And less motivation to read. Like when students don’t get to pick what they read. As you can imagine, just like with anything else, they have a little bit less interest in it.”

For Doyle, the big focus should be on what truly causes low reading proficiency, especially when the curricula keep changing but the levels do not.

“Can you really say it’s that single factor? Or is there something we don’t intrinsically discuss that needs to? Because it’s decades now that we still aren’t seeing these numbers move. And if you don’t have a child reading at grade level by fourth grade, you’re dooming them to diminished returns where they’re not going to recover.”

Clarification (May 21, 12:45 p.m.): In response to Martina Meijer’s claims, DOE rep Nicole Brownstein says that, while typing isn’t part of the program, there are classes and Individualized Education Programs (IEPs) for those who struggle with typing.