A litany of problems have plagued recent elections for an important panel that helps to oversee the city’s educational system — and detractors are fuming over the controversial and dysfunctional process.

The city’s Department of Education employs the voulenteer-based “Panel for Education Policy” (PEP) which allows parents and concerned citizens to advise the city on major issues affecting schooling in the Five Boroughs.

Members of PEP collectively vote on things such as large DOE contracts, Gifted and Talented programs, the citywide school budget, and more.

But the selection process for PEP members was plagued by timing issues, technological problems and rampant miscommunication, according to some.

The PEP selection process

PEP is made up of 23 members — 13 selected by the mayor, five selected by the city’s borough presidents, and five selected by the city’s Community Education Councils.

The latter five spots became the main source of contention.

In Brooklyn, there are 12 Community Education Councils (CECs), made up of volunteer groups covering the schools within a specific geographic area within the borough.

The heads of those CECs are meant to pick representatives from a pool of candidates to serve on the PEP.

With five spots up for grabs, each borough would get to nominate one member to serve on the PEP.

In Brooklyn, there were three finalists for the spot to represent the borough:

- Stephen Stowe, the CEC 20 President

- Dr. Meryhem Bencheikh-Ellis from CEC 13

- Jessamyn Lee, a PTA member at Williamsburg’s PS 84

Lee was ultimately chosen, but not before a series of alleged missteps with the process, which was overseen by the city’s Department of Education.

Timing issues

The DOE had known since last June that the election process for PEP members needed to be in place. That is when the education law passed the state legislature, and expanded the number of PEP members, creating the new makeup of the panel.

But, before they could get the ball rolling on elections, the incumbent PEP members had to vote on the changes to Chancellor’s Regulation A-670 as well, which took several months.

After that, there was a 45 day waiting period before voting for the new members could actually begin, meaning an election would not be possible until November at the earliest.

Making matters worse, the lack of time and public solicitation for candidates putting their name forward made it so there were not enough applications — forcing the CECs to ask for an extension.

They wanted to move the election for PEP members until January, but the DOE insisted that elections take place by the end of 2022, so that new members would be in place to start the year.

“Per the state law, we had until mid-January to vote,” said Camille Casaretti, the head of CEC 15. “Many of the Brooklyn CEC Presidents wanted the election to be held after the new year but the DOE pushed forward…There was no reason to vote in December right before a holiday break.”

The short timeline, which did not need to be in place, also meant that fewer candidates than would be expected had actually put their name forward.

Other than determining the timeline, the DOE did not provide any help to the CECs for the process, said Paullette Ha-Healy, a member of a separate council on Special Education.

“These are all volunteers,” said Ha-Healy. “They’re CEC Presidents. They’re still running their CECs and they are given the additional task of doing this, with very little help from the DOE, other than them telling them ‘this is the timeline, you gotta get it done.’”

With all the delays, and the impending holidays, the three finalists in Brooklyn to represent the borough on the PEP were given a chance to make their case on Dec. 19 — and the CEC heads needed to pick between them on the next day.

Technology problems arise

Brushing up against a DOE-decided timeline, the CECs responsible for picking the PEP representatives also ran into several technological problems.

Several CEC voters say that web links for the candidate forum videos (where PEP candidates made the case for themselves) did not work on the day they were meant to vote.

Additionally, the six of the city’s CEC presidents (three from Manhattan and three from the Bronx) were not able to access the voting links, leaving them unable to vote at all.

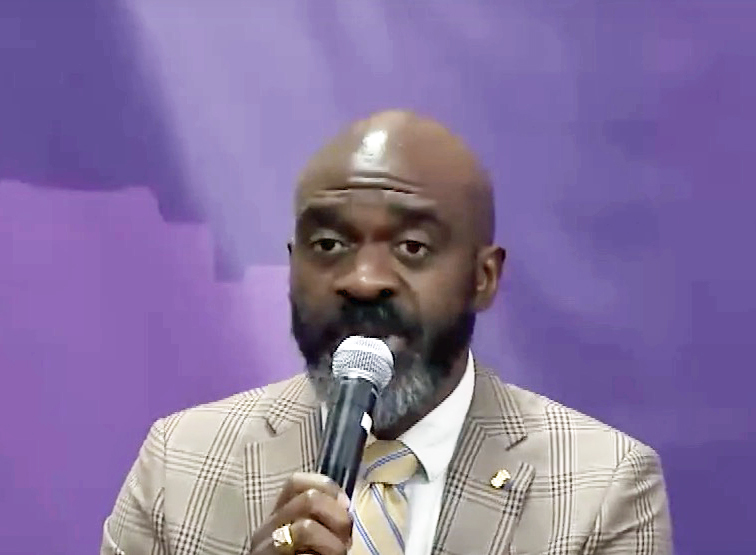

NeQuan McLean, the head of CEC 16, and a member of the nominating committee that whittled down the field and selected the final three candidates for the post, called the situation both avoidable and unacceptable.

“It’s been a disaster,” McLean said. “[The DOE] was in charge of this election and they botched it.”

“What kind of voting process do you do in 24-hours?” he added. “Last year when this process happened, they called people and said ‘hey, don’t forget to vote’. There was none of that done this time.”

DOE responds

In response to a request for comment to the DOE, asking about the short timeline, the technological issues (which left six CEC heads unable to vote) and the lack of clear communication, a spokesperson defended the process.

“Family engagement and voice is critically important to this administration. 81% of eligible voters cast their vote for borough-based parent PEP members. The elections were run within the restrictions of state law and PEP-approved regulations, which were extensively discussed and communicated to both CEC presidents and PEP members,” said Nathaniel Styer.

Casaretti, though, blasted that statement, arguing that the exclusion of six CEC heads was nothing to be brushed off, and the rushed-vote right before the holidays was unacceptable.

“I can’t understand why anyone at the DOE would find it acceptable to exclude six out of 32 CEC Presidents from the PEP member vote rather than allow for a more reasonable timeline that would still fall within the limits of the law,” Casaretti said. “The vote could have waited until after the holiday break. 19% is an enormous percentage of families who are now unrepresented. All 32 CEC Presidents should be entitled to vote.”

Casaretti went so far as to demand a redo of the vote.

“No Council or District should go unrepresented. There are no excuses to be made. The DOE’s interpretation of this law has been negligent, and a conversation must be had regarding a do-over vote as soon as possible.”

That is unlikely to happen, though, and the new body of the PEP appears to be moving forward.

As a silver lining, the next election for new members of both the PEP and the CECs citywide are both within the next six months.

McLean said he simply hoped that the process would go more smoothly next time around.

“I hope that moving forward, we do this right,” McLean says. “This role is very important and that parents’ voices are heard is very important. This did not go well. [So] when we start this over in March, it is done correctly.”

For her part, Jessamyn Lee, who was ultimately selected by Brooklyn’s CEC heads to serve as the Borough’s representative on the PEP, agreed that the process could have been better.

“I hope things run more smoothly,” Lee said. “I hope there is more direct advertising to the parent community across the city to garner a greater pool of parents to nominate themselves to really ensure that the PEP ultimately reflects the constituency of New York City families.”

Nevertheless, she said she’s ready to fight on behalf of Brooklyn’s students in her new role.

“I’m very eager to serve the students of Brooklyn,” she says. “I know the system inside and out. I feel like I’m really qualified because, in addition to having worked as an ESL teacher for a very long time, I am also the parent of a student with disabilities. I feel like I can amplify the points of two very under-represented, underserved populations.”