The Department of Environmental Protection returned to the city’s planning commission last week for a review session and public hearing after receiving recommendations and approval from Borough President Eric Adams to move forward with the Owls Head combined sewer overflow facility in Gowanus.

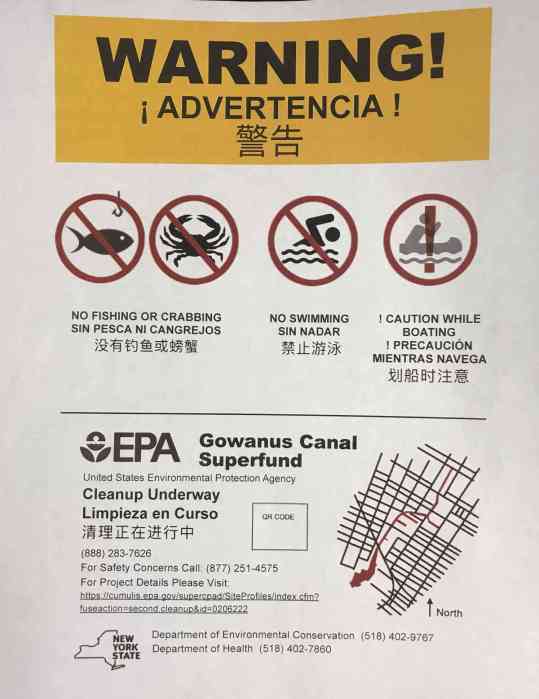

DEP was first pushed to construct the two facilities nearly 10 years ago, after the Gowanus Canal was designated a Superfund site and slated for cleanup by the federal government. While the primary focus of the cleanup is dredging the 10 feet of “black mayonnaise” — a noxious sludge of chemicals, sewage, liquid tar, and decomposing organic matter – and capping it with clean sediment, the Environmental Protection Agency said the continued overflow of sewage and wastewater into the canal was unacceptable and ordered the city to build the two catch basins, which will store overflowing water and pump it to treatment plants, rather than allowing it to flow back into the canal.

Head End, the larger of the two facilities, holding about eight million gallons, will be located at Butler Street and Nevins Street, and construction is slated to begin as early as January 2022. Owls Head will hold about four million gallons, and is expected to be built on the salt lot alongside the Sixth Street turning basin, near Second Avenue.

The borough president’s say in ULURP is, technically, advisory, though if they vote no, a supermajority of nine City Planning Commission commissioners must vote yes to move the project forward.

“We would hope our recommendations are largely adopted by the City Planning Commission and the City Council when they take their binding votes on ULURP items,” said Jonah Allon, a spokesperson for the borough president. “The Office of the Borough President continues to advocate for binding commitments that reflect the needs of local communities in every land use item we take up.”

Some of Adams’ conditions matched the ones the community board made in July, including maintaining regular contact with the board, adhering to guidelines set by the EPA and committing to providing publicly-accessible open spaces at both sites.

The EPA has already warned DEP that they may face “serious penalties” as a result of construction delays after the agency revealed that Head End may not be completed until 2032. If the tanks are not in operation until years after dredging is complete, waste may build up on top of the new cap, officials said last year, and the city will be financially responsible for paying for additional cleanup.

Having identified the four privately-owned lots they’ll use for Owls Head, DEP is now looking to purchase them, which would displace six industrial businesses, according to Allon. The community board and the borough president’s office both asked that DEP engage with those businesses and assist them in relocating.

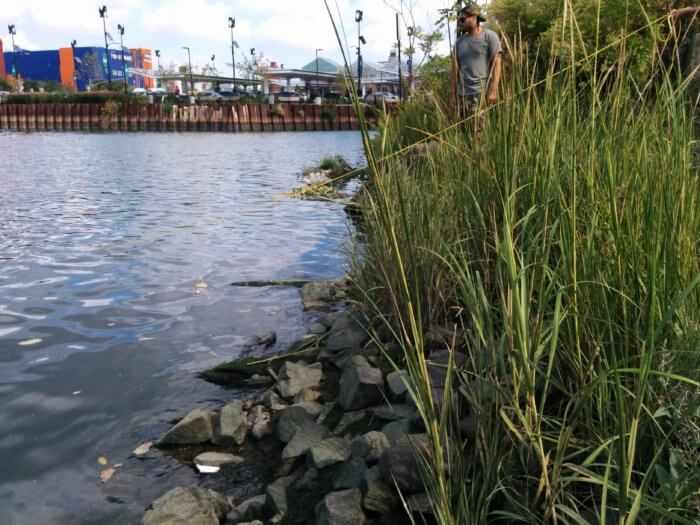

Edward Timbers, a DEP spokesman, said the agency has already had multiple meetings with those businesses, and that consultants will work alongside them to find new locations, navigate leasing, and provide reimbursement for moving costs. The salt lot on the site also hosts a compost drop-off center, sponsored by the city’s sanitation department and nonprofit organizations Big Reuse and the Gowanus Canal Conservancy. The lot is also home to the conservancy’s plant nursery, gardens, and outdoor classroom, and an outdoor classroom.

The beep’s office made specific mention of Big Reuse and GCC, asking that they be relocated to “prevent disruption of stewardship and education programs.”

“The salt lot has been this place where we can make those connections, where we can get middle school students excited about the urban water system, and the challenges we face, and how they can be part of the solution” said Andrea Parker, executive director of the GCC. “We just want to make sure that while we do all this incredible remediation work, we’re continuing to provide room for education and interpretation and engagement.”

The organization has been working with DEP to find several potential temporary sites, Parker said, all owned by the city, and are working to make an agreement with one of them. In addition to being the home of the gardens and classroom, Parker said the salt lot is an important central location where their volunteers can pick up supplies and head out to work in the neighborhood.

In a July letter to Community Board 6, Parker asked that DEP consult the conservancy as they designed the facility, proposing a map that included space for the existing compost and garden facilities, along with a boat launch, pedestrian bridges, and public green spaces.

Conceptual layout diagrams do show space for composting projects and open space on the salt lot. The city sanitation department will also be able to maintain existing salt and snow plow storage sites, though final designs for Owls Head are not expected to be completed until 2023. DEP currently estimates that construction for Owls Head will take five years in three phases — wrapping up in about 2028.

“The design of the salt lot is an incredible opportunity to really address not just the infrastructure needs but also to make space for education and interpretation, and restoration,” Parker said. “The DEP is making room in the design process for that, we want to see commitments through the ULURP that really identify those uses as uses that will be part of the design.”