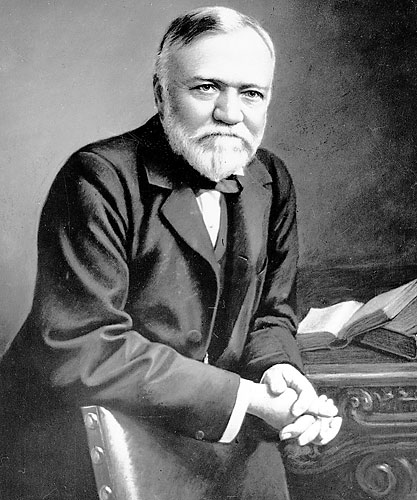

The future of the Brooklyn Public Library system hinges on a simple question: what would Andrew Carnegie want?

The steel tycoon financed the construction of 21 libraries across the borough more than a century ago, promoting literacy and gifting Brooklynites iconic gilded-age architecture, but as his 18 surviving structures age and libraries transition from halls of books to hubs of technology, the inheritors of Carnegie’s charitable legacy face tough fiscal choices.

The Pacific branch opened on Fourth Avenue in 1904 as Brooklyn’s first Carnegie library, but the building is becoming a threat to the magnate’s vision, according to Brooklyn Public Library officials who want to sell the property just steps from the Barclays Center and use that cash to move into a new, modern facility two blocks away.

“Andrew Carnegie’s real legacy is not necessarily bricks and mortar, but the idea of access to the incredible wealth of information and knowledge contained in a library for everybody,” said Brooklyn Public Library vice president for government and community relations Josh Nachowitz, who wants to put the Classical Revival-style structure on the market rather than shell out $11 million of the $15-million annual system-wide maintenance budget to fix it up.

Cutting the losses by treating the historic Pacific branch as the system’s sacrificial lamb would let the Brooklyn Public Library focus on services and programming at its other 59 branches — helping the library chain live up to Carnegie’s ideals, officials say.

“If Carnegie were alive today he would be very desperate to see the Brooklyn Public Library provide the best services in the most accessible building in the most modern facility,” Nachowitz said.

That modern facility would come in the form of a slightly bigger branch inside a planned 32-story tower developed by Two Trees Management Co., which would be brighter, airier, and better suited to today’s library-goers than the current Pacific branch, according to officials.

“It’s a failing building,” said Brooklyn Public Library chief librarian Richard Reyes-Gavilan, who noted more than half of space in the current Pacific branch is made up of small rooms and chambers not open to the public or usable for operations because books are now processed at a single central location. “It’s past its useful life.”

The sale is expected to generate $10 million or less, which would cover the interior build-out of the new branch that could wind up looking something like Kensington’s newly opened $14.9 million branch, with large multi-purpose reading rooms, plenty of natural light, and cutting edge technology, said library trustees.

Any cash leftover after the new library’s construction would go back into the borough’s library system through an agreement with the city.

But the move would likely be the death knell for the historic Pacific branch, which is not landmarked.

Activists are decrying the plan, saying the red brick building is just as important as the books and programming inside.

“This was truly a gift to the city of New York in an attempt to really create an institution, which is why the Carnegie libraries were designed by some of the premiere architects of the time — they served to uplift through their architecture as well as through their mission,” said Simeon Bankoff, the executive director of the Historic Districts Council.

“The preservation of stand-out pieces of architecture that were gifts to the neighborhood is a really important thing to maintain,” said Bankoff.The Park Slope Civic Council has pushed to have the Pacific branch landmarked — a bid the Brooklyn Public Library says it will not oppose so long as the building’s sale could still generate enough cash to cover the move.

Library officials have met less opposition in their similar plan to sell the 1960s-era Brooklyn Heights branch, which needs $9 million in repairs, and insist they have no plans to put any other Carnegie buildings on the market — claiming they are only considering unloading the Pacific branch because of the confluence of its remarkable location and uncommonly high needs.

But the only Carnegie buildings truly safe from future development are the Dekalb, Park Slope, and Williamsburgh branches, which are protected by landmark laws.

The Carnegie buildings boast large, multi-paned front windows, red brick or limestone facades, stone steps leading to prominent entrances adorned by lampposts or lanterns, and classical ornamentation including columns, pilasters, and pediments.

And they were apparently put up to last: 30 percent of libraries borough-wide were built by Carnegie and a century later they only require 31 percent of the $230 million needed to conduct overdue repairs.

But library officials say many of the old edifices fail to meet the needs of modern-day patrons — and unloading the Pacific branch will help the chain remain a vital cultural institution in a time when city budgets are anything but certain.

“We’ve got to take some control of whatever we can control and this is just one smidge of what we can hopefully control,” said Reyes-Gavilan. “It’s crucial for us to stop being victims and leverage whatever we can so that the library can remain relevant for people for the next hundred years.”

Selling the branch — even if it means demolition for the 108-year-old building — is a move that Carnegie, a businessman above all else, would have wanted, according to author David Nasaw, who penned the simply titled “Andrew Carnegie” biography.

“Carnegie was not terribly interested in the architecture of these libraries — he wanted the local people to decide where the libraries would be,” said Nasaw of the tycoon, who donated $5.2 million — equivalent to more than $2.7 billion today — after his retirement in 1901 to establish a branch library systems citywide. “What was most important to him was that a library be open, be accessible, have books and reading materials.”

Nasaw said that Carnegie was by no means a preservationist who would have nostalgic commitment to the buildings funded through his philanthropy — in fact he was hands-off with the architects who designed them.

At most, he would have wanted passersby to be able to recognize a building as a library from the street, the biographer said.

“He would have wanted the libraries to be a public symbol,” said Nasaw. “But Carnegie is a businessman — he’s going to look at the bottom line and he’s going to say if it costs $11 million to keep this old building up to code and if for $11 million you could build a library that’s twice as big or that has twice as many services then he would go with that.”

Reach reporter Natalie Musumeci at nmusumeci@cnglocal.com or by calling (718) 260-4505. Follow her at twitter.com/souleddout.

Photo by Elizabeth Graham

Photo by Elizabeth Graham