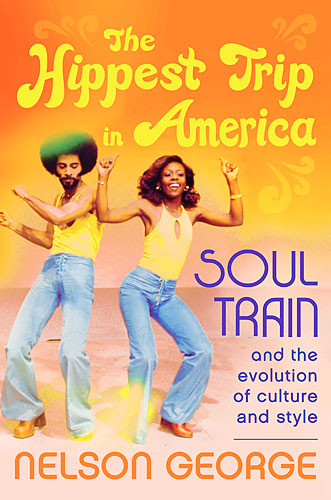

Nelson George knows a thing or two about soul. For the past four decades, he has been one of the preeminent critics of African-American pop culture, focusing his attention over the years on iconic figures such as Michael Jackson and James Brown, to the worlds of basketball and hip-hop. His latest book “The Hippest Trip in America: Soul Train and the Evolution of Culture and Style” takes a journey through the history of the titular TV program, which for 35 years introduced America to the most of-the-moment musical acts around. On March 26, George will discuss the book at Bedford Stuyvesant Restoration with former “Soul Train” dancer Tyrone Proctor. The Brooklyn Paper spoke with the writer and filmmaker from his home in Fort Greene to discuss the impact of “Soul Train” on American culture, and Spike Lee’s recent comments on the gentrification of his neighborhood.

Robert Ham: Do you remember the first time you saw “Soul Train?”

Nelson George: I don’t remember the first time, but I do remember watching it as a child. I grew up in Brooklyn on Saturday mornings we’d watch the show on this little color TV. What I remember about it was how bright and colorful it was. The colors of the set and the vibrant outfits, much brighter than you’d see in New York or Philadelphia.

RH: Do you feel like “Soul Train” gets its due as being such a huge force in popular culture?

NG: Anyone who thinks of the ’70s and dancing and clothes and style, thinks of “Soul Train.” It pops up everywhere from “Austin Powers,” where Beyonce has a “Soul Train” scene — her sister Solange does a video like that. Even a car commercial I saw this winter. Clothing designers still reference the show. So, it definitely lives on. That key period from 1971 to 1985, those years still resonate.

RH: What did you learn interviewing dancers from the show?

NG: I think just the conditions that they danced under. They were pretty rough. On the one hand, they had an incredible opportunity and some incredible exposure, but on the other hand, they weren’t paid. Many of them had full-time jobs and would come dance on the show on the weekends for some fried chicken and some soda. There were a couple of dancers that were really irritated about the fact that they weren’t paid, they were in a union, and didn’t have any health care attached to their work. I was also surprised how many of the dancers are still active today, traveling the globe and doing workshops related to some of the dances they popularized on the show.

RH: Do you think a show like “Soul Train” could survive in today’s oversaturated media world?

NG: I don’t know. I know that’s something that folks like Nick Cannon and Questlove are trying to figure out, to see if the desire is there for dance on broadcast TV. Dance is not going away, but the internet has become the equivalent of “Soul Train.” Just the other day, my niece who is in her mid-20s and another teenager took me to YouTube to show me this dance and that dance. That’s what “Soul Train” was — it was street dance being spread around the world.

RH: Having been a longtime Fort Greene resident, how do you take Spike Lee’s recent comments about the gentrification of the neighborhood?

NG: He said the same thing in my documentary “Brooklyn Boheme” three years ago! Almost exactly word for word. So, I’m very aware of his feelings. I’ve lived in the neighborhood since 1985 and have seen it go through a couple of permutations. The central thing is that it’s frustrating to feel your community being cheated. The neighborhood was red-lined at one point so the banks and financial institutions would not support homeowners here. You couldn’t get a bank loan to fix their staircase or pluming. The root of that anger is in that institutional lack of commitment. I also know that I’m benefitting from a lot of the new theaters and the new restaurants. The history of New York is a history of change. The white working-class community turned into the black working-class, and so much of the culture of the city was produced by children of working-class parents, thanks to their access to museums and clubs and the like. If you take that community of people out of the city, what does that mean for New York’s future?

“Nelson George” presents “The Hippest Trip in America” at Bedford Stuyvesant Restoration [1368 Fulton St. between New York and Brooklyn avenues in Bedford-Stuyvesant, (718) 636–6900, www.restorationplaza.org]. March 26 at 7 pm. Free.