Before the Wonder Wheel and Cyclone thrilled visitors to Coney Island, the amusement hub boasted much more peculiar entertainment, such as the California Red Bats that baffled guests in 1897. Patrons would pay a quarter to enter a dark theater, walk up a few steps to a platform, and discover what turned out to be a stack of broken bricks.

The mastermind behind this scam was George Tilyou, the creator of Coney Island’s second amusement park, Steeplechase Park, in the 19th century. His there’s-a-sucker-born-every-minute credo banked on the idea that those fooled would convince their friends to follow suit.

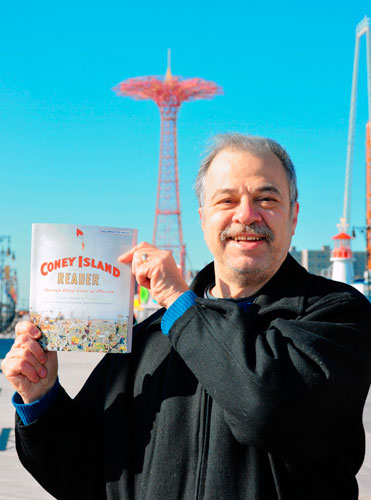

“He counted on people wanted other people to get tricked, the same way that they were,” said Louis Parascandola, the author of “Coney Island Reader: Through Dizzy Gates of Illusion,” which hits bookstores this month.

That’s one of the many facts Parascandola learned while compiling writing and newspaper articles for the tome that verifies what we’ve all known for years: Coney Island is anything but boring.

The book is organized into four main periods of Coney’s history: the beginning through 1896, the era of the three great amusement parks, the “Nickel Empire,” and the years of decline. Parascandola organized the writings by the periods they describe and not when they were written, so a story written in 1958 titled “The Master Showman of Coney Island,” a sketch about Tilyou, sits in between articles published in 1907 and 1909, when Tilyou was still conning people out of a quarter at Steeplechase Park.

“I want to restore Coney Island’s history,” he said. “To do that, you need to see what people were saying at the time and how its influence has continued.”

But what people were saying was not always positive. Coney had a reputation for crime and violence in the early 20th century. An excerpt from the historical novel “Dreamland,” by Kevin Baker, describes the island as immoral and a safe haven for those on the outskirts of society.

The earliest article included in the “Coney Island Reader” also happens to be written by the most recognizable author. Walt Whitman. “Clam Bake at Coney Island,” published in 1847, chronicles a trip to Coney. Before even arriving to the island, Whitman is overwhelmed with excitement and asks himself, “Could moral ambition go higher, or mortal wishes delve deeper?”

The drive to assemble the “Coney Island Reader” grew out of a college course Parascandola was teaching on Coney Island’s history at Long Island University about five years ago. His brother John would commute from Maryland most weeks to assist, and while gathering materials for the class, they were both constantly amazed at all the new documents and photographs they found.

They were adamant about mixing literary writings and newspaper articles because they felt people needed to read both in order to understand the area’s history. The fictional stories paint a picture of what Coney Island looked and felt like at different times, while firsthand accounts verify that the fictional stories were based on reality.

Growing up in Brooklyn, the Parascandola brothers made the trip from pavement to seashore two or three times a year with their parents and two sisters, until Steeplechase Park closed in 1964. After their parents died and their sisters became sick with cancer and Alzheimer’s, they decided to compile the book to commemorate a place they all enjoyed together.

“It represented our family and the things we shared in Brooklyn,” Parascandola said.

He believes the magic of the People’s Playground’s heyday still exists in the living history — Nathan’s Famous hot dogs, the Cyclone, the Wonder Wheel.

And there is the Parachute Jump. Built in 1939 for the World’s Fair, it is a relic of Steeplechase Park. The ride hasn’t worked since Steeplechase closed, but it looms over modern-day Coney as the highest point on the former island.

John Parascandola rode the Parachute Jump before it closed in 1964. It dropped riders from the top of the tower, strapped into a seat attached to the tower by only rope, with nothing but a parachute to slow the decent to the ground. Louis sees the now-inoperable tower as an important reminder of the old Coney Island that he is working to preserve and restore.

“We look at it as the Statue of Liberty of Coney Island,” Parascandola said, referring to himself and other Coney Island preservationists. “Every time I see that thing my heart starts to race a little.”